On top of everything else that happened in 2016, it wasn’t a great year for my blog posts. I’ve managed to update the blog at least once a month for the past few years but since my post on the EU referendum at the end of June, I’ve only managed one more — an overdue review of Isabel Costello’s debut novel (albeit a long one).

Looking back, despite my best intentions, I’m still not exactly sure why I’ve not managed to keep up the previously modest level of posting activity. It’s probably prioritisation by default as I’m still writing and doing just as much interesting stuff in between. There’s also been various developments with the novel that I’m not really able to publicly blog about on here.

But one thing I’ve kept doing, mainly because it’s nowhere near as time-consuming as blogging, is taking lots of photos.

So in the spirit of a picture telling a thousand words here’s a photographic run through 2016 with a bit of commentary along the way

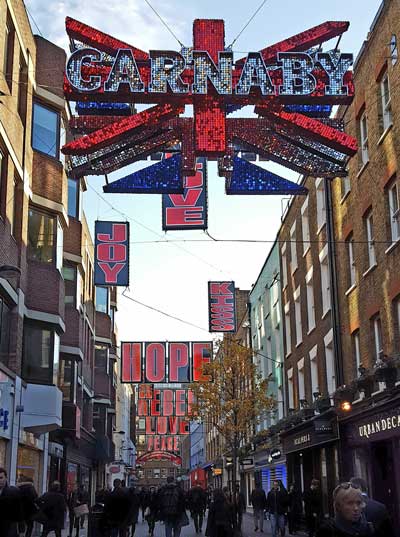

Perhaps one reason for being distracted from blogging is that I’ve spent the past year working in Soho. For example this place is just around the corner…

…and even though it’s no longer the groovy Swinging Sixties, there are enough spontaneous ‘happenings’ around where I work for me to have grabbed the odd evocative photo, like this one…

I walk past this iconic place almost daily (it was interesting to see it featured in The Apprentice this year)…

…and along here often too (and at the moment it’s worth walking to the end of Carnaby Street to the pop up shop set up by the V&A Museum in association with their You Say You Want A Revolution Exhibition).

And there’s plenty of things to be distracted by nearby — like the amazing Christmas angels in Regent Street…

…or just weird London scenes like this.

Sometimes it’s been restorative to occasionally get away from it all and lie (albeit briefly) under a tree on a patch of grass in one of those rare summer lunchtimes.

I don’t say much here about the ‘day job’. Until late 2015 that was partly because I might have been taken out and shot if I said too much! OK. That was meant to be a gross exaggeration about working in a government ministry but the way Theresa May’s government is treating its civil servants then perhaps it’s not. Nevertheless, I have a hazy recollection that I may have signed the Official Secrets Act, not that I had access to much secret stuff but I did work almost literally at the heart of government. I walked daily through the doors of a large ministry — one that was often on the front page of the newspapers — and shared lifts with cabinet ministers.

While I wasn’t exactly Sir Humphrey, I was given invaluable direct experience of the the way government works.

And in terms of writing benefit, I gained insider knowledge of the criminal justice system, through working with the police, HM Courts and Tribunals system ( even doing some work for those seditionary “enemies of the people” in the UK Supreme Court).

It’s all fantastic material should any of my future novels head in the direction of crime or politics.

The organisation where I now spend most of my nine-to-five working hours couldn’t be more different. I won’t go into specific detail but it’s a media-tech company (hence the Soho base) and uses a lot of clever technology to encourage people to pay money to look as absurd as the people below…

(Apparently the gun isn’t on sale yet.) Actually, the VR (Virtual Reality) experience is so immersive that these people won’t care how they look from the outside. I’ve tried VR and it’s convincing. I predict that the technology could be on the cusp of going mainstream. And don’t take my word for it — creating a VR game was another activity to be featured on this season’s Apprentice.

2016 produced some unexpected recognition for my writing — non-fiction this time.

I was elected (or admitted or whatever they do) to full membership of the British Guild of Beer Writers. It might seem surprising to some that this organisation even exists but it has a few hundred members, including household names and virtually every author of a book on beer or pubs or contributor on the subject to any broadsheet newspaper or TV or radio broadcast.

I was elected to full membership on the basis of published examples of my writing (which I don’t tend to talk about much on this blog) so it’s a huge honour to be in the company of so many illustrious and expert writers in that field.

Here’s the image that adorns my entry in the BGBW website directory.I’m hard at work at the beer tasting side of the job!

Being a member of the guild let me rub shoulders with the movers and shakers of the beer writing world at their awards ceremony, including the odd, hairy beer-loving celebrity.

But even though my blog posts may have slipped off the radar, I’m still writing a lot of fiction, even on holiday in France (see below).

I could get used to that lifestyle.

With various things happening with The Angel (which, as it’s a book, have been invariably slow moving) , I’ve been hard at work on another novel. A heavily adapted version of the new novel’s opening even won a prize in the Winchester Writers’ Festival Writing Can Be Murder crime writing awards this year.

I’ve kept in touch with many writing friends, enjoying their successes, for example, with winning stories at Liars’ League and other writing -related developments that can’t be blogged about. I’ve also kept up my involvement with the RNA (see previous post) and received another great critique from their New Writers’ Scheme.

By providing a series of non-negotiable deadlines every few weeks, my membership of a writing group in London has proved invaluable. I’ve propped myself up and carried on writing well into the early hours on several occasions by working on a piece from the new novel. In the summer I carried on once or twice for the whole night — going to bed (briefly) once that sun had risen.

The standard of my fellow writing group members is generally excellent (one reason why I burn the midnight oil to try to make my submissions at least presentable) and we’re very fortunate that the group is run by someone who’s a professional writing tutor at City University and novelist.

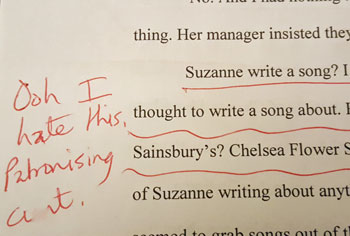

The group’s feedback is excellent — both illuminating and honest — although not usually as brutally frank as the comment below.

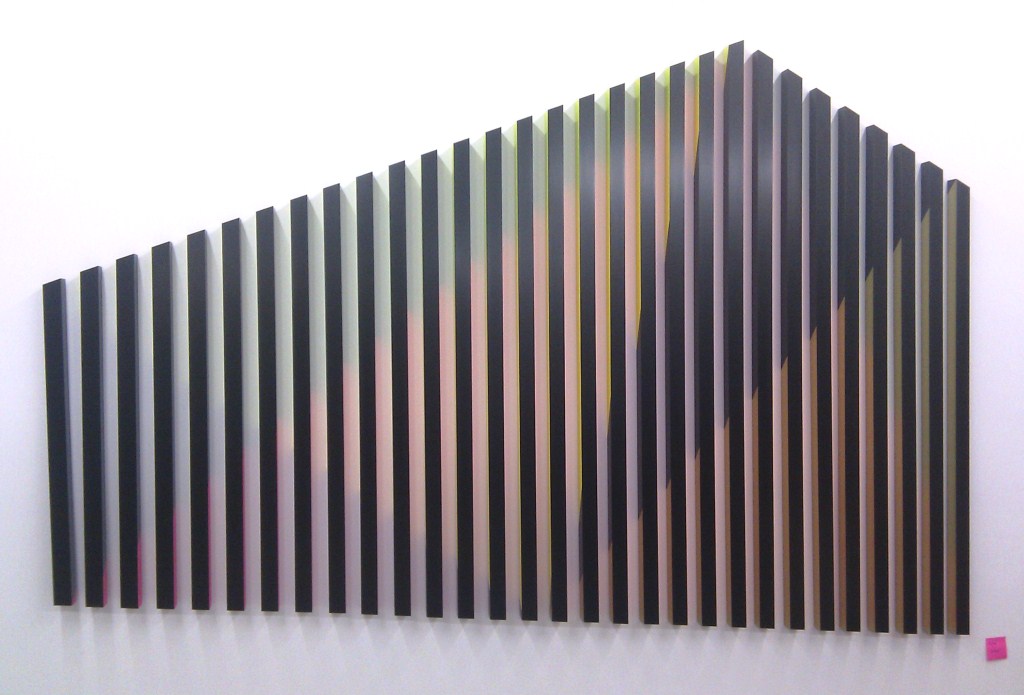

I’ll save details of the current work-in-progress for another post. However, the next few photos might give a clue about some some of the things I’ve been doing that could act as background research for the world of the novel.

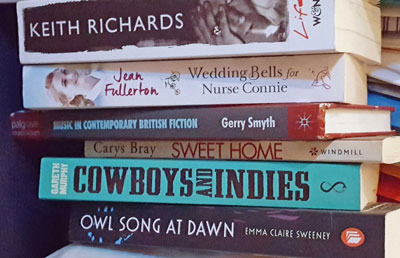

Here’s a shot of a pile of books waiting to be read…

…and below is another example of my methodical approach to shelving books (Owl Song At Dawn is an excellent novel published this year by my old City University creative writing tutor, Emma Claire Sweeney, who organises Something Rhymed — see earlier post).

I’ve not been to any music concerts quite as jaw-dropping at Kate Bush’s Before the Dawn (whose recording of the shows was released a few weeks ago and allowed me to relive sitting right in front of the spectacle — and the sonic battering of Omar Hakim’s drums — listen to the extended version of King of the Mountain on the CD and you’ll know what I mean).

But during the year I’ve been to see a couple of other giants of music from the past thirty or so years. Most recently I saw Nile Rodgers, also at the Hammersmith Apollo, who performed an incredibly energetic set of hits by Chic, Sister Sledge, Diana Ross and others (several of which I heard a few days later being played from loudspeakers in Hyde Park’s Winter Wonderland) and he also played an obscure favourite of mine, Spacer, originally by French singer, Sheila B.

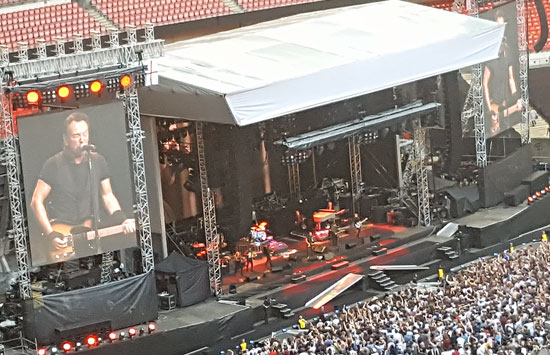

Seeing Bruce Springsteen live has been one of those bucket list items I’ve always wanted to experience so I took my opportunity when he played Wembley Stadium in June along with 80,000 or so others. Elsewhere in the stadium were Bruce fans and writing acquaintances (and tweeters) Louise Walters (whose second novel is published imminently) and Pete Domican.

Springsteen’s stamina and his rapport with a stadium audience are awesome. He played from around 6.30pm to just before 10pm, non-stop. The sound where I was sitting in the south stand was fairly ropy but I was more dumbfounded by the behaviour of the people in the (not very cheap) seats around me. As can be seen from one of the earlier photos, I like a pint of beer, but many of the mostly middle-aged, middle-class audience seemed to treat the Springsteen show like a visit to a very expensive pub — possibly reliving their rose-tinted memories of some student bar. They constantly shuttled to and from the very expensive Wembley bar and then, inevitably, to the toilets. While loudly declaring their devotion to ‘The Boss’, some dedicated fans danced with their backs to the stage and got so drunk they either had to leave before the end. Some wouldn’t have remembered it anyway.

I was a little dubious in advance about another music-related experience in the summer — visiting the Latitude Festival in Suffolk in July. I wanted to go mainly to see Grimes: who’s nothing to do with the music genre grime, but a hugely innovative and original musician from Canada whose music defies any easy description — being both catchy and experimental — and mainly, but not exclusively, electronic.

It was described as one critic as being simultaneously like everything you’ve ever heard reassembled and remixed in a way which sounds like nothing you’ve ever heard before. That strikes me as something interesting to aspire towards in writing.

What massively impresses me about Grimes is that, with the exception of a couple of guest vocalists, she writes, sings, plays all the instruments, produces and engineers her recordings. I never get bored listening to her most recent album, the brilliant Art Angels . ‘Don’t be boring’ is another great rule of thumb.

Her live performance was equally original and self-reliant, accompanied by only a couple of dancers and her recent collaborator, Hana, on guitar (on left in photo below).

While waiting for Grimes, I had an unexpected opportunity to see Slaves, a two man guitar and drum modern-punk group. While the group themselves would be unlikely to dispute that their music is the opposite of subtle, their performance was amazingly good humoured (with songs about commuting like Cheer Up London or fat-cat bankers ‘Rich man,

I’m not your bitch man‘) and created such an engagement with the audience that the FT reviewer described it as ‘life affirming’.

Before Slaves I was blown away by an electrifying performance by Christine and the Queens. Along with Art Angels, I must have listened to Chaleur Humaine (Christine and the Queen’s debut album) more than any others this year. I went to one of their two shows at Brixton Academy in November for a repeat of the live experience.

I’ve always had a fondness for French electronic music (Air are another of my favourites). When Héloïse Letissier (Christine is her alter-ego) announced ‘Welcome to the French disco!’ at the start of Science Fiction, one of my favourite tracks, it seemed an appropriate riposte to the narrow-minded bigotry and xenophobia that has scarred other aspects of 2016 which far too many despicable politicians and newspaper editors spent much the year cultivating.

Christine and the Queens are inclined to do unexpected cover versions live and I had the spine-tingling moment of serendipity when they covered Good Life by Inner City, at the time of its release in the late 1980’s a much-underrated track, but one of those tracks everyone seems to know — maybe because of the almost improvised vocal line that wanders where it’s least expected? But I guess Christine and the Queens may have picked it as an antidote to all 2016’s other shit?

At the other end of the socio-political spectrum to Slaves’ music, I’d been wary of Latitude’s reputation as the Waitrose of music festivals — with rehabilitated hippies regressing to the behaviours they liked to say they indulged in their youths. And, indeed, during the day there was indeed a scattering of baby-boomer types trying to press-gang their extended families into enjoying the festival in a conspicuously worthy way.

Boomer grandchildren were transported around in flower-garlanded trolleys like this one…

…and as it got later the place became more like a pop-up Center Parcs, except the vegetal aromas in the forest weren’t coming from wood burning fires. Eventually as the night wore on and the older people retired to their luxury tents the sound-systems and DJ sets attracted large, bouncing swathes of younger people, like moths to the flashing lights.

Wandering through the woods I came across a series of artists’ nstallations — and immediately recognised the brightly-coloured faces of David Shillinglaw’s work (whose studio I visited a couple of years ago with Love Art London). He’s an exceptionally friendly person and showed me around his unmistakable collection of positively painted sheds, which transformed into a music sound-system after dark.

I’d visited Latitude for the music but was most impressed by the festival’s showcasing of all types of art. When I first arrived I stopped off at the the literary arena to listen to an author interview with the Bailey’s Prize winner, Lisa McInery. It was a nice touch to have a bookshop on site.

Coming a few weeks after the EU referendum result, Latitude was a refreshing distraction that emphasised the pleasures found away from the poisonous and vindictive political atmosphere. Ironically, the industries represented by Latitude — art, music , comedy, dance, theatre and literature — are those in which the UK is an undisputed world leader (reflected in much of the content of this blog over the past few years) but seem undervalued by the closed-minded, xenophobic, anti-intellectual, expert-dismissing philistinism of the pro-leave bigots.

The opposite of a huge festival like Latitude is the proverbial gig in the back of a pub. I spent a fascinating evening in July on the Camden Rock’n’Roll Walking Tour, led by Alison Wise. Covering the amazing musical heritage of a relatively small part of London between Camden Town tube station and the Roundhouse near Chalk Farm.

I was especially pleased that we stopped off in several pubs on the way. Each pub had a strong association with one of Camden’s music scenes through the last few decades. The Hawley Arms was Amy Winehouse’s local (with the likes of the Libertines as regulars), The Good Mixer was where the leading Britpop bands hung out, the areas around Dingwalls and Camden Lock have many punk associations and the Dublin Castle in Parkway launched the careers of Madness and many other early eighties bands.

And here’s me with Molly from Minnesota (the only time I’ve ever met her) inside the Dublin Castle in a photo taken by Alison at the end of the tour.

It’s surprising how many of Alison’s tours round Camden and elsewhere are filled by tourists from overseas rather than native Brits or Londoners. Even though I’d worked in Camden for five years a while ago I still learned a lot from the tour — all relevant for writing purposes too. Alison also does Bowie Soho tours and album cover pub crawls which I’m sure are excellent.

I’ve read a lot of books over the year, although nowhere near as many as I’d intended. I’ve worked my way through a lot of musical biographies and autobiographies, including Chrissie Hynde’s frank Reckless, the bizarre Paul Morley prose of Grace Jones’s I’ll Never Write My Memoirs and the beautifully written (and non-ghosted) Boys In The Trees by the wonderful Carly Simon.

A few Sunday Times bestselling blockbusters have also made it on to my reading list, mostly out of curiosity to understand the reasons for their success. After having read them, in most cases, I’m not much the wiser.

So I’ve been busy, enjoying lots of new experiences and taking many more photos than those above. It’s even more worthwhile then those experiences to settle into the subconscious, interact and collide and spark off little bits of unexpected inspiration I can later use in my writing. And to help the process, there’s nothing like taking a bit of time out and reflect.

So the last photo in the post was taken on a long walk between Christmas and New Year s the sun was setting over the Chilterns — a hopefully prescient, peaceful image to usher in 2017.