In some ways the novel featured in this blog could be interpreted as a love letter to this country. Much of it is set in the England of shady country lanes lined with cottage gardens and of thatched pubs on village greens serving real ale under indomitable oak trees.

If you have a strange feeling you’ve seen the village idyll in the photo above somewhere before then it’s because you probably have. I took it on Haddenham village green a couple of weeks ago. It’s a village a few miles from where I live which is frequently used for film and TV. It’s a staple location for Midsomer Murders, which is phenomenally popular abroad – apparently the most popular TV programme in Sweden.

This is the vision of this country we export to the world. It’s peaceful, gentle and tolerant. It’s the inspiration for The Shire in The Lord of the Rings, Constable paintings and Thomas Hardy novels. Generations have treasured the romance of the British landscape and the values it represents. And it still exists.

Alongside that bucolic version of England, the novel also celebrates the vital, ever changing cosmopolitan buzz of London and our other major cities – the likes of Shoreditch, Hackney Wick and Digbeth. These are places where the fabric of the area is transformed into a permanent arts festival (see the photo I recently took just off Brick Lane below – the artist who painted the famous crane is Roa – a Belgian).

This type of amazing street art, which is renewed on an almost daily basis, is merely the visible manifestation of a culture that attracts young, creative innovators from around the world. They bring an amazing energy that powers initiatives from web start-ups and craft beer breweries. One industry where Britain punches way above its weight is the creative industry.

Both contrasting visions of Britain complement each other – in fact, they depend on each other. Creativity benefits from a bedrock of tolerance and stability. Traditional Britain is prevented from becoming stale, insular and inward-looking.

Similarly, the two principal characters in the novel view Britain from these different perspectives. Despite his flair for cooking inventive, internationally inspired food, James is as solidly British as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.

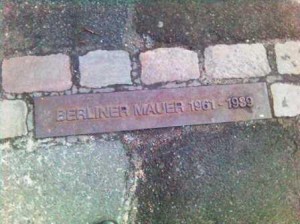

Kim views the country through the eyes of an outsider. A passionately Anglophile German, she is more fluent and accurate in English than most native speakers. In common with other young Europeans she views the Second World War as something out of her school history books but nevertheless she immensely respects Britain’s pivotal role in creating the peaceful, civilised Europe of the post-war era.

She adores English eccentricity, humour and imagination — and she falls deeply in love with an Englishman who symbolises all the values she admires about this country – values that were celebrated with such unforgettable verve during the London 2012 Olympics (about which there are many posts on this blog).

While remaining a proud German, she sees views herself principally as a European and a Londoner. One of the questions asked in the novel is where will she decide to call home.

The country in my novel is something to be immensely proud of. However, I’m fearful that after this week’s EU referendum, my novel might need to be re-categorised as historical fiction – as the start of L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between famously says: ‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.’

if you want only to read about writing and the novel and itself then stop here – or possibly skip to the final paragraph or two.

.jpg?1464595911)

However, as the setting and characters demonstrate, questions of national identity thrown up by the referendum strike at fundamental themes in the novel.

I rarely comment on politics on this blog, nor in normal circumstance would I want to bang on about my views. I’m extremely interested in politics but my views aren’t extreme. However, aspects of the way this referendum campaign has been conducted have made me angry enough to write the following long blog post. And if you have the patience to wade through it you might discover, if you’re interested, something about the life experiences on which I’ve partly based my views on the referendum.

My sole previous political blog post was written way back in January 2013 on the same EU referendum subject. My views on the referendum itself have barely changed from those I expressed in that entry, which was prompted by David Cameron’s announcement of what must have seemed at the time to be a clever wheeze to give him an easy life in parliament. Read it here. Much of it has turned out to be quite prescient, particularly when I anticipated the tone of the debate.

However, I don’t think I expected to be so depressed by the shrill and personal tone of this EU referendum debate. Most fundamentally, it seems very un-British. Lying, mud-slinging, personally insulting opponents rather than discussing arguments have no place in the Britain that I’ve grown up in and written about with fondness. The repugnant tone, which seems to have its roots in the poisonous atmosphere of US politics, is hopefully an aberration – a mass neurosis like the 2011 riots that will pass and be buried in history.

Cameron has gambled badly, trying to present himself as both a Euro sceptic and a pragmatic Europhile and has allowed the Leave campaign the opportunity to present the EU as the source of virtually every problem the country faces.

Meanwhile, the Remain campaign has pushed a negative narrow economic message about the risks of leaving, rather than the benefits of staying, which has allowed its opponents to label genuine concerns as ‘Project Fear’. Jeremy Corbyn could have done a much better job of explaining the benefits that the EU has introduced for employees (holiday pay for one thing).

While the EU is by no means perfect, it’s not responsible for the extraordinary catalogue of misery that its detractors claim.

If this was a referendum with a question that would allow us to opt out from the brutal, economic insecurity caused by globalisation and the capricious power of global capital then I would certainly be campaigning to leave. The novel starts with James rejecting the pointlessness of his job, which merely seems to shift vast sums of money from account to account in a multi-national bank.

Several years after the economic turmoil of 2007-8, many in this country people still justifiably feel disenfranchised and disadvantaged. And I’ve been one of them. I suffered redundancy as a result of the credit crunch and I know what it feels like to have dependants to support and a mortgage to pay – and no foreseeable source of income.

Perhaps it’s this experience but I wouldn’t want my vote to increase the likelihood of putting anyone else in that position (if that’s what I judged the consequences might be).

.jpg?1464595941)

I respect and share many of the genuine concerns that have attracted people to some of the arguments put forward by the Leave camp. But in almost all of these cases I have not seen any convincing plans or evidence that walking out of the EU into the unknown will do anything to solve these concerns. In fact, the likelihood is that the UK would be in a worse position after leaving the EU with respect to most of them.

Even the issue of immigration, which I agree that mainstream political parties have ineffectively addressed, is unlikely to be addressed by leaving the EU. We can’t change the geography that places us twenty miles across the channel. As for the idea we have open borders with the EU, the last few times I’ve driven to Europe (I last went in April), I’ve had my car searched inside and out for stowaways and the passport checks on the UK side have been extremely thorough.

Although I have an MBA, which means I’ve had some education in economics, finance and the way businesses operate, I wouldn’t claim to know much at all about the workings of international trade deals and negotiations. But because I don’t, I’ve read extensively about the pros and cons of EU membership.

I would particularly recommend The Economist’s very balanced coverage. They have a free downloadable 20-page PDF guide on their website which contains a wealth of impartial data. Unlike most of the national papers that have come out on the Leave side, The Economist is independent of any influence from a proprietor.

Nevertheless, despite the magazine’s editorial stance usually being sympathetic to the liberal, free-trade wing of the Tories who are campaigning for Brexit, they are unequivocal that the UK should remain. One of their columnists predicts the consequences of implementing the many contradictory claims made by the Leave campaign would be disastrous both for Boris Johnson and company and the country:

“It will be fatal for their careers, and for the reputation of British politics in general, if they follow the economically sensible course only to face a huge outcry from nativist voters who feel that all those promises on immigration have been betrayed again. Even aside from the economic consequences of a Leave vote (and read this LSE demolition of the Brexit case), the immediate future for Britain could be very ugly indeed.”

I could write hundreds of blog posts further expanding on my views on the referendum and the conduct of the campaign – and I may well do in the next few weeks. However, I want to present a largely positive case for why I believe Remain is by far the most desirable outcome.

In my previous blog post I described how I worked for many years travelling extensively in Europe representing the interests of the UK division of a large multi-national company to its German owners and I describe the often tortuous process involved.

The Germans may have been autocratic and slow to make decisions but their business made more money than the UK’s and German profits probably kept the UK division in business in certain years. And it’s my experience of negotiating with Germans that makes me sceptical that they’d make the UK a generous leaving settlement. But we cooperated and made it work. I couldn’t have done that job if I’d needed to apply for a visa for every 19-hour long day I worked when I flew on a day trip to Europe.

Despite our many differences, I made some great friends of decent, friendly Europeans of all nationalities. And we shouldn’t underestimate the importance and influence of the English as the business language of Europe. It gives us a natural advantage as mediators and conciliators.

I love travelling to Europe. I love experiencing European culture. As a British tourist, I also like the convenience of the Euro. However, I was sceptical about the UK joining the single currency (as I believe that financial and political policy are too inextricably linked). But we’re out of the Euro and can never be forced to be part of it. Fact. (Ironically, the most plausible way that the UK would end up in the Euro would be to leave the EU and then to be forced to accept the currency as price of being readmitted if everything went disastrously wrong.)

I don’t love the EU as an institution. Some of its officials appear almost as insufferably arrogant as the UK politicians who have been most vocal in the referendum debate. The EU should have made far more of a positive case about how it values the UK as a member (but then it would have been shouted down for ‘interference’).

Germany’s economic dominance is also a potential concern. Chancellor Merkel didn’t consider the consequences for other EU countries in last year’s asylum seeker crisis. But the UK is an essential counterweight to Germany inside the EU.

The decision making process may be sclerotic and opaque. The ability of national parliaments to veto major decisions makes the process slow but it also means that the UK can veto the Leave campaign’s apocalyptic visions of a European army or Turkey’s accession.

The EU is far from perfect. But they’re our neighbours. We will need to live alongside Europe whatever the referendum decision. Having suffered from inconsiderate neighbours myself, I know how preferable it is to compromise in order to coexist peacefully. As A.A. Gill’s brilliant article in last week’s Sunday Times magazine said, leaving the EU on the unrealistically rosy terms painted by the Leave campaign would be like trying to negotiate a divorce with your ex that still entitled you to have sex every weekend.

I’ve worked in central government and have seen the EU’s influence for myself. For three years in the last government I worked in the HQ of the Ministry of Justice in Petty France, Westminster. I shared lifts with Ken Clarke and listened to Chris Grayling’s droning staff addresses. I worked alongside senior civil servants. I was involved with prisons, H.M. Courts and Tribunal Service and electronic tagging among other areas – exactly the things the tabloids say we’ve lost control over.

I visited the UK Supreme Court, the Royal Courts of Justice, the Law Commission and met the people who literally write the laws of the land (they have special software to do it).

How much meddling by unelected EU bureaucrats did I encounter? None. My work was seen by ministers and senior judges. No one from the EU had any involvement whatsoever. In a department of maybe a hundred people, one person did a part-time role in which she travelled to Brussels occasionally to inform them about what we were doing. That was it.

Perhaps there are other areas of the Ministry and the legal system where there’s more EU influence but of the areas where I have first-hand experience, the EU influence was negligible. Don’t believe what you read in the papers.

A decade or two ago, claims of an incipient European super-state might have been more credible. But the UK has opted out of the two most fundamental aspects of EU integration.

We’re not in the Euro and we’re not part of the Schengen passport-free agreement. The UK hasn’t been ordered around and humiliated. It’s achieved extremely significant concessions and I’d anticipate this is the way the EU will evolve – an inner core of the Eurozone with the remainder in a looser federation. If the debate was more honest, I believe many Leave voters would realise we don’t need to “take back control” because we never lost it in the first place. Nor is there any prospect of doing so.

Unlike the majority of voters, I’ve also lived outside the EU. I’ve spent almost a year each living in both Australia and the US. There was a huge amount of red tape involved in obtaining visas, social security numbers, driving licences and so on to live in the US. California was a wonderful place to live but you wouldn’t want to be ill there without any health insurance. One of the many underrated virtues of EU membership is the reciprocal free health cover in all member states.

One of the many unknowns about leaving the EU would be what happens to such benefits enjoyed by ex-pats. The NHS would be faced with the biggest crisis in its history if hundreds of thousands of pensioners returned from Spain because they were no longer entitled to free Spanish health care at exactly the same time the EU nationals who form a large part of the NHS work force would be leaving — voluntarily or not. The Spanish prime minister has said ending reciprocal healthcare is a possibility. It’s certainly something that would have to be negotiated.

While I’ve had considerable experience of other countries and cultures, I’ve always had a deep-seated, possibly irrational belief, that this country is the best place in the world to live and that to call yourself British is something to be proud of – that, on balance, we’ve contributed hugely to what’s good in the world – culturally, diplomatically, scientifically, artistically and in so many other spheres. When I hear the opening of Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus, which is based on timeless British folk melodies, I feel a connection with the country deep in my core that seems to reach back centuries (listen below).

I was born and brought up in the north-west. Some of my family has roots in the north-east. I went to university in Birmingham. I live in the south-east and work in London. I’ve experienced the incredible diversity of people and culture in this country.

And most of all I’ve valued the country’s tolerance, the people’s politeness and their fundamental sense of justice and fairness. This is a place that has always welcomed others and I’m disgusted that some immigrants who make a positive contribution to society have been made to feel unwelcome just by the tone of the referendum debate. Imagine how they’d feel if we voted to leave. The electorate can’t pick and choose the immigrants we want to avoid offending (“oh, we didn’t mean you“). Put it this way, if I lived in Europe and all I heard in the media was about whether they wanted to “take back control” from foreigners I think I’d start looking at my options. And, as always, the people with the most skills will have the most options.

Large parts of the country – London and the labour intensive farming businesses in the east of England – depend on EU migrants as their workforce. Imagine the red tape and bureaucratic interference involved in forcing companies to get government approval (to count the Australian-style points) to employ EU nationals – businesses already complain the process for non-EU nationals is holding them back.

It’s been said that the EU referendum is as more a vote about how what kind of a country the UK wants to be and how it sees its place in the world rather than the specifics of the relationship with the EU.

If so, I desperately hope that the country doesn’t opt to change into a place that nurtures the small-minded, vindictive, divisive nastiness we’ve witnessed in the last few weeks. It would undermines all that’s good about British values.

I don’t think a Leave vote would be an apocalyptic disaster. In fact, I suspect we’d end up with some messy compromise that gave us single market access without any say in it and still needing to pay the EU and accept free movement of labour. It would be a worse deal than we have at the moment, achieved through a period of needless divisiveness. It’s the subtle, insidious damage that would be done to the character of the country I’ve set my novel in that most concerns me.

Both campaigns have been culpable by exaggerating. This has obscured the fact that are honourable people with great integrity on both sides. Nevertheless, I believe any objective observer would judge the majority of the self-serving, spiteful vitriol to have originated from certain dark parts of the Leave campaign. Allied to a reluctance to engage with objective facts, this coarsens the whole debate. Once the touch paper is lit all sides get angry. I’ve seen the most appalling abusive trolling on Facebook and Twitter of people who are merely expressing their opinion.

There’s such a weight of opinion, ranging from all twenty Premier League clubs through to J.K. Rowling (who wrote a good piece today about how she recognises the techniques she uses to create fictional villains being employed by Leave), all major UK car manufacturers, the Governor of the Bank of England and the President of the United States on one side of the argument. All the other side can do is dismiss the judgements as those of ‘experts’ (as if that discredits them) or to retort ‘they would say that anyway’. To me that suggests the rational, logical argument doesn’t seem that finely balanced. Desperate people resort to desperate measures.

In a general election the voters are usually remarkably effective at working out which party represents their best interests. This referendum is unprecedented. People have no historical reference points.

When it’s a battle between ‘the grass is greener’ and ‘better the devil you know’, it’s a conflict between emotion and reason. And having apparently failed on the economic argument, the Leave campaign has chosen to inflame the basest of emotional responses with its inflammatory rhetoric on immigration.

I’m scared that good people are being manipulated and deceived by cynical opportunists into voting for something that will undermine what’s great about this country. Everyone is entitled to vote according to their conscience and without intimidation – it’s what a democratic society is founded upon. Equally, however, democracy fails when voters are blatantly misled and when an extremely complex question is twisted into a debate that merely sets one group of people against another.

Returning to writing, which is what this blog is meant to be about, I’ve been considering alternative titles for the novel. I’m undecided at the moment so won’t reveal my favourite here. However, it relates to accidentally inflicting an injury on yourself due to a lack of concentration in a domestic setting (how’s that for a crossword clue?) – and dealing with the painful consequences. Not a bad metaphor for the EU referendum, although with that decision the damage would last decades rather than hours.

Boris Johnson once said his view on cake was that he was ‘pro-having it and pro-eating it’. That seems to sum up his failure to address any of the difficult choices the country would need to make to fulfil the incoherent and contradictory claims made by the Leave camp.

If something sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Don’t be fooled. We might not have a chance to be fooled again.

.jpg?1464595905)