And I’m wondering where on earth did 2013 go? Certainly not writing lots of blog posts — it’s been a very lax six weeks since the last update — but if I get this post published today then I’ll at least have posted a blog entry in each month of the year.

Writing more frequent (and shorter) blog posts will have to be one of 2014’s New Year resolutions. I’ve had several absolutely fascinating (he says) posts mulling in my mind over the past few months but I’ve not found time to commit them to cyberspace.

At this reflective time, it’s tempting to look back and wonder what happened during the preceding 365 days. In many ways I’m doing the same day-to-day as I have for the last few years. I’m still writing, tweeting and doing a day-job. I’ve been enjoying my time in London as much as I did at in 2012 (when I wrote a post last New Year’s Eve celebrating what a remarkable experience 2012 in London had been).

I started this blog in earnest in January 2010 — when its principal purpose was to follow my progress through the City University Certificate in Novel Writing. I doubt that I’d have expected to be still blogging about my continuing development as a fiction writer — three years of an MA following the City course would have seemed a long slog back then.

So, in some ways it seems that little is different but these are probably the most superficial. In a deeper sense this blog has recorded much more profound changes — the huge amount I’ve learned about writing, how the skills I’ve developed have matured and how my perspective is much better aligned to the commercial realities and demands of the publishing world.

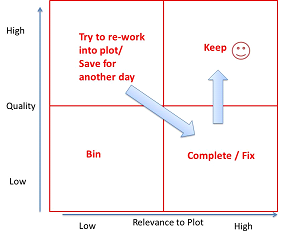

I spent time this summer revising some of the first sections of the novel. These were written back in 2010 and, while reading the material was surprisingly pleasurable, I feel I’ve improved as a writer very significantly.

And, as well as learning and honing a craft, I’ve enjoyed some brilliantly sociable and stimulating times with so many other creative people along the way.

I’ve been so busy that it’s easy to lose sight of two major achievements that happened in 2013: I finished my three-year MA Creative Writing course and, in doing so, completed as good a draft of my novel as possible. Sure it would benefit from some more work — I’m sure virtually all writers would like to polish their work were it not for deadlines — but I’ve reached that fundamental milestone.

And it’s a novel that I’m proud of having written — with characters I haven’t tired of in over three years (the emotional wrench of saying goodbye to them is the flip side of this coin) and imho the novel says many things worth saying about life in contemporary Britain. Possibly the best compliment of the 2013 was when one of our ex-City writing group, who’s not afraid to be critical, read the whole manuscript and said it was ‘a terrific read’.

Completing a novel is such a massive undertaking that I have huge respect for anyone else who shows the necessary qualities of perseverance, motivation and self-belief required, especially if fitting it in around work or other commitments. That’s in addition to any innate writing ability. I don’t particularly agree with the aphorisms often tweeted that suggest that talent is commonplace whereas it’s hard work that’s rare but completing a novel is a certainly a slog that requires a lot of sacrifice.

I’ve been careful to say I finished the MA course — another achievement in persistence — but I’m yet to find out if I’ve passed. I’ll get the official results in June so hopefully, this time in 2014 I can say I’m in possession of a Masters degree in Creative Writing.

Now the course is over, it’s probably fair to say that, for all of us, taking a long course like an MA or the year-long City Certificate (now Novel Studio) isn’t the fastest way to write a novel. There’s a lot of time spent on absorbing best practice from established writers’ texts, workshopping and critiquing with other students, engaging in discussion, learning about aspects of the publishing industry, writing in other forms (as I did for my screenplay in the MA) and writing assignments. It’s surprising there’s enough time left to even make a start on the novel. However, all who complete these courses should emerge much better equipped to go on to write more successfully in the long-term.

We’re promised feedback on our completed novels in mid-January. This seemed a rather distant date when I submitted the novel in early October, when my instinct was to try to finish work on it and move on to something new as soon as possible. However, if the forthcoming feedback is as comprehensive as the university have suggested then I guess I ought to be prepared to go back to the manuscript and act on any recommendations. The novel should have been read by at least two markers and also externally moderated so a fresh perspective will be really valuable (especially when compared with the cost of other manuscript appraisal services).

And I finally met up with one of my virtual coursemates. About six weeks after the novel submission deadline I was in Birmingham visiting some classic pubs with friends and took a detour to the Black Country to have a very pleasant chat in person with Kerry Hadley. We met, appropriately for my novel, at a famous pub — The Vine in Brierley Hill — otherwise known as the Bull and Bladder. What a spectacular sunset too. I’m sure that during 2014 a publisher would like to snap up Kerry’s excellent novel from the MA course. Maybe I’ll finally get to meet up with Anne in 2014 — another who survived until the bitter end?

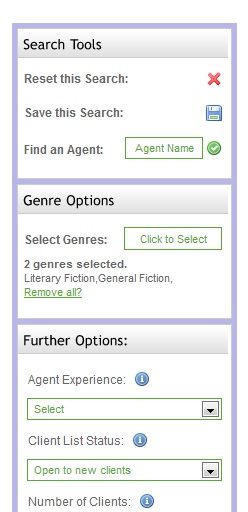

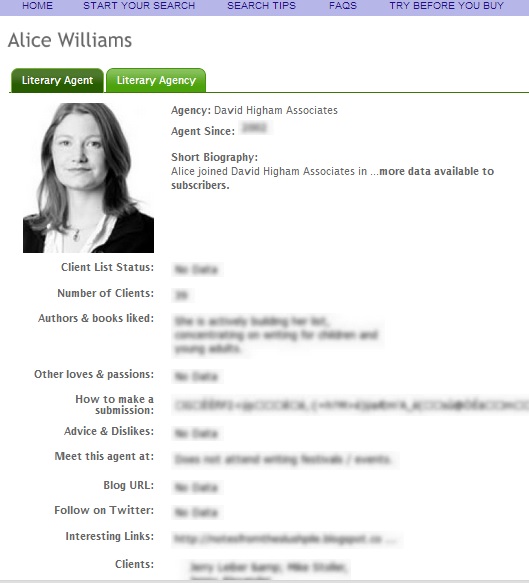

So if 2013 was about completing the novel and the MA course. 2014’s resolutions are going to be about trying to get it published — a process that’s probably going to be long, difficult, frustrating — the archetypical emotional roller-coaster. Time to develop a thick, calloused skin? As mentioned previously, I’m not going to catalogue the submission saga on the blog. However, I’ve spent a lot of time researching the process at networking events like the York Festival of Writing (where I received some excellent one-to-one feedback from a couple of agents), London Writers’ Cafe (I slurped a large G&T at the Christmas party) and London Writers’ Club. I’ve also exchanged notes with many other writers over Twitter and email so I have a reasonably informed idea of which agents I perhaps ought to approach. In most cases I’ve seen the agents speak or had short conversations with them myself, which makes the process less daunting (or perhaps more so in some cases).

(Having said that, should an agent I’ve not met or listened to stumble across this blog is interested in reading some of the novel then please get in touch!)

2013 has also been tremendously encouraging for me as several writing friends and acquaintances have achieved success — showing that signing with an agent and getting a book published happens to people who’ve followed a similar route to myself. I wrote a post in the late summer about the great news of Rick Kellum from my City course being signed by Juliet Mushens. I heard recently that Bren Gosling, also from the City course, and who’s often commented on this blog, has also been taken on by a leading literary agency.

Also, Isabel Costello (who I last saw at Anastasia Parkes’s ‘interesting session’ at the York Festival of Writing — see post below) of the excellent On the Literary Sofa blog I’ve mentioned on this site, has also recently been signed by Diana Beaumont of Rupert Heath for her debut novel. In all the above cases, I know the writers have worked extremely hard on revising and reworking their novels over a long period and their achievements are very well deserved.

A few weeks ago I also met with Jennifer Gray from the City course who’s been working extremely hard on her rapidly growing number of children’s books. In 2013 she had the fantastic news of being shortlisted for the Waterstones’ Children’s Book Prize for Atticus Claw Breaks the Law — the first of the Atticus series. A search for Jennifer Gray on the Waterstones website comes up with at least ten books — including the Guinea Pigs online series and the intriguing Chicken series which will be published in 2014.

Talking to Jennifer has given me an insight into the commercial demands of the publishing world — with deadlines for submitting, revising and proofing new titles stretching many months ahead. She’s also a practising barrister and has a family so I’m in awe of her industry — again another example that, in addition to talent, published writers need to put in a lot of hard work. In my case, with course deadlines no longer a factor, I perhaps need that sort of external discipline to give me a kick up the backside every so often (not that Jennifer needs one herself, I’m sure).

Like many other writers, I’ve also been juggling the demands of the ‘day job’ with making time for writing — which often feels like I’m burning the candle at both ends — sometimes trying to eke out time to write from what’s available in the rest of the day, even maybe a token effort of writing a few sentences.

In many ways the writing is like taking on a second job — one with a long, unpaid apprenticeship except with myself as boss to sporadically crack the whip. It often seems I have to snatch time to write: on the train, at lunchtimes (sometimes in St. James’s Park), unearthly hours of the day and night and at the expense of more conventional weekend pursuits (such as the urgent repairs required to my disintegrating garden shed — I’m sure Roald Dahl’s famous writing shed didn’t have a gaping hole in the roof).

Nevertheless, I’ve managed to write tens of thousands of words in 2013 — and also cut several thousand too in the process of editing, revising and proofing a completed draft. I must have found a writing routine that’s sufficiently accommodating. Of course, it remains an ambition to make writing bring in enough income so that I can have some dedicated, professional writing time. On the other hand, I guess putting in so many hours up to this point shows how much I must enjoy writing for its own sake and also my belief that this work will pay off in the long run.

So I start 2014 hoping that this might be the year that all that time writing and studying will pay dividends. Whatever happens I’m looking forward to starting to write the new novel that I’ve been writing in my head and jotting down ideas for while completing The Angel.

But to see in the New Year I’m going to do some well-earned research — and, considering the main setting of the novel, where else to do it but in the local village pub? I even wrote a scene in the summer set at The Angel’s chaotic New Year’s party. I hope no-one’s end of year celebrations are quite as bizarre as my fictional pub’s musical celebration — singer-songwriter Jason’s ‘whiny-voiced set about dusky maidens and mysterious sex beasts’.

So good luck and the best of wishes to everyone who’s read the blog or who whose company I’ve enjoyed in any writing-related (or other) way during the last twelve months. Let’s look forward to 2014 and hope it brings all of us something of what we’re hoping for.