The last post dwelt on art at the celebrity and ‘major gallery spaces’ level  (as Time Out describes them). But my novel is about an artist trying to make a living, someone who doesn’t have the reputation of Picasso or Hirst nor has the resources or the inclination to re-stage the battle of Orgreave. To get an appreciation of how art is produced and sold at the more accessible end of the market I went along to the Affordable Art Fair in Battersea Park in March (handily getting a discount on entry with my Art Fund card!).

The Affordable Art Fair differs from the London Art Fair by maintaining a price ceiling of £4,000 on all works for sale (although I was shown an under-the-counter £20k picture by Billy Childish), which means that those of us who don’t run hedge funds might have a prospect of picking up a decent piece of work for an amount that’s, well, affordable.

I only had a lunch-hour to look around the huge pavilion with hundreds of stands from galleries all over the country so I was intrigued by the ‘Egg Timer Tour’ offered by Love Art London. This was a free tour of ten of the most interesting stands which was guaranteed to take no more than an hour — and to ensure punctuality Chris Pensa, who ran the trip, took along a clockwork egg timer. When it buzzed, it was time to move on, at pace, to the next stand.

(One of the stands we visited had miniature figures within glass containers created by Jimmy Cauty, ex-of the KLF — which is an interesting connection with the Jeremy Deller exhibition mentioned in the previous post.)

I thoroughly enjoyed the tour — it was a fast-moving (literally) and very approachable introduction to the contemporary art world. After the tour I learned more about Love Art London — they organise events approximately once a week, for people interested in art, often visiting galleries for private tours, having Q&A sessions with artists in their own studios and so on — ideal for my writing research purposes. Chris sold membership to me instantly when he said the whole thing was so friendly and informal that they usually end each event in the pub — often drinking with the artists. This organisation could have been created specifically for me!

The first event I went to — a private viewing of Glasweigian duo littlewhitehead ‘s installations in the Sumaria Lunn gallery near Bond Street — was fascinating from my perspective of learning how artists interact with their galleries and collectors. Unfortunately, with the gallery being close to the Mayfair hedge fund types, the pub afterwards was so packed with suited chinless wonders five-deep ordering Roederer Cristal at the bar that I didn’t have time to order myself a drink before I needed to get my train home.

Fortunately, at the next event, I was successfully able to pop into the pub — the Owl and Pussycat in Shoreditch, just round the corner from Kim’s fictional studio in my novel — with fellow Love Art London members and Chris Pensa himself. He told me that he’d set up Love Art London after working for a while at Sotheby’s and he found it very rewarding to provide this sociable and fun way of becoming familiar with the London art world — he also provides a similar service for corporate clients — a different sort of experience than the normal team away-day.

We were in Shoreditch after having had a private viewing of work exhibited by the shortlisted artists for the Catlin Prize. Art Catlin curator, Justin Hammond visits shows by students graduating from British art schools and picks forty artists to feature in a publication — the Catlin Guide — which has become known as an overview of new British art.

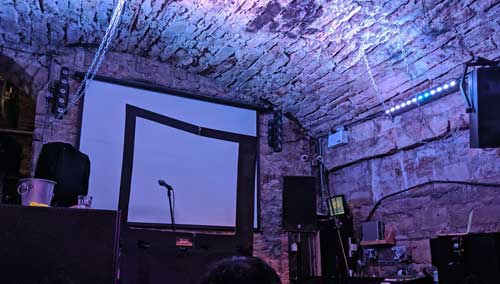

Ten of the artists were selected to exhibit in a gallery in Londonewcastle, which appeared to be a warehouse currently undergoing conversion in Shoreditch (I know this as I had to be sneaked round the rest of the building to go to the toilet, having had a very quick couple of pints near Monument on the way) and four of these artists gave us a short talk about the work they had on show, which was fascinating for me in trying to improve my understanding of the way young artists work in London.

Jonny Briggs‘s works were mainly in what was probably the most conventional form — photography — but his photographs had a very surreal quality. He explained that he explores themes related to his awakening as an adult in his teenage years — and rather than alienate his parents as is the stereotype — he involves them in his art. His father appeared in several works — sometimes wearing a latex mask of himself — and providing a bronze cast of a toe for one non-photographic piece.

Max Dovey’s work as a performance artist earned him a place in the Catlin prize shortlist — and he exhibited something that resembled a fixed monument both to an event he’d organised and to mark the passing of the technology that event had marked — the ceasing of analogue television broadcasts. Final Broadcast, a short online video, records a party Max had organised to celebrate the last night of analogue television transmission in the London region (the last in the country). The Last Day of TV, his Catlin exhibit, was a series of five sets of five boxed videotapes which were recordings of the last hours of the type of transmission that had first started about 75 years ago. The videocassettes, which are an almost archaic item themselves, were set on a wall like an apt combination of library books and tombstones.

Julia Vogl, who was named as the overall winner of the Catlin prize last week, designed a very clever participatory exhibit — Let’s Hang Out. She constructed a Mondrian-style grid of black and white, both on the floor and against the wall, like three sides of a cube. This was surrounded by carpet tiles, stacked in about half-a-dozen different colours.

A slogan on the wall challenged viewers to declare what they’d do in a spare ten minutes by tossing a square carpet tile into the grid. A key on the wall assigned colours to activities, which included: ‘Tweet’, ‘Call Mum’, ‘Daydream’ and, the only activity whose colour I remember, ‘Masturbate’ (a yellowy-gold). Â I think these gold tiles were winning when we saw the installation, which says something about the visitors to the exhibition — probably their honesty.

On her website, Julia Vogl categorises Let’s Hang Out  as a social sculpture and it captures the Zeitgeist of the times – with its physical, participatory interaction encouraging viewers to share their ‘status’. And the use of such familiar and (literally) workaday material as office carpet tiles also emphasises the democratised perspective of the work (apparently the artist used to work in political polling). Let’s Hang Out was last week declared the winner of the Catlin Prize 2012 — by judges who included the art critics of The Times and Time Out.

But there was another prize, awarded to the artist who polled highest in a public vote — entries were either submitted online or in a ballot box at the entrance to the exhibition. This was won by Adeline de Monseignat. Her work Mother HEB/Loleta also explored touch and texture. The work comprised several glass spheres partially buried in sand — exploring the connection between the smoothness and solidity of glass and the graininess and liquidity of its component material. Most of the spheres were small, set around a much larger glass ball about 70 cms in diameter. Pushed against the inside surface of the bigger globe was something with an organic, furry texture which was folded in irregular ridges like the surface of a brain — and if one looked at the sculpture for long enough, this inner material could be seen to move up and down almost imperceptibly — as if it were alive.

The sculpture had a surreal but soothing other-worldly quality, as if some alien life-form had descended into a desert-scape. With Adeline’s permission, I’ve linked through to a photo of a similar installation on her blog — Emerging.

- Adeline de Monseignat – ‘Emerging’ © Adeline de Monseignat http://adelinedemonseignat.com/

Adeline gave us a very illuminating talk about how she constructed these unique objects — which I referred to as furry orbs. The material inside was old fur coats, picked up from charity shops and the large glass sphere was custom made by a glassblower and was likely the largest of its kind in the country (any other large transparent sphere would usually be made out of perspex for weight and resilience purposes).

With its understated ‘breathing’, juxtaposition of the sensuality of fur on the inside of the sphere and the sterility of glass on the outside, and the spheres’ resemblance to eggs scattered in a barren desert, the work raises questions about some of the most fundamental issues — such as fertility and the creation of life.

From my novel’s perspective, it was interesting that the two prizewinners were both young women artists who’ve moved from abroad to work in London — Julia Vogl is from the US and Adeline is from Monaco — so it’s a relief that my character is credible in that respect. However, I’m probably never going to a character in a novel written by me that can come up with the sort of innovation and insight that any of these real-life young artists have shown — Kim mainly works in painting with an interesting side-line in photography.

But one thing that’s great fun about writing about art is trying to give enough of a description so the reader can then imagine the work — creating imaginary artworks that exist in the individuals’ minds but that have never actually been physically created — a concept that’s reminiscent of Keats’s famous lines in Ode to A Grecian Urn: ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter.’ (Later recycled in the 1980s by ABC as ‘The sweetest melodies are an unheard refrain‘.) Both basically mean that the conception of an artwork is always more perfect than any eventual physical realisation — something also very true of writing.

And so I ended up drinking with the Love Art London people and a few of the Catlin Prize artists outside the Owl and the Pussycat pub. I’m back in Shoreditch again on Friday for Love Art London’s graffiti tour, which I’m looking forward to enormously — again it will be excellent research for the novel. As I prepared to walk back to Old Street station, Chris pointed out some work immediately around the Londonewcastle Gallery — including a stickman by Stick — who’s apparently something of a mysterious celebrity.

I’m not sure if Redchurch Street, Shoreditch is the ‘land where the Bong-tree grows’Â but it’s where, for the next few days until 25th May, the works by all ten of the Catlin Prize shortlisted artists can still be seen — and I believe it’s free to get in.