Two stand-up performers I saw at Edinburgh delivered sets with a theme in common — “escaping” a profoundly working-class background in the geographical backwaters of middle-England to become comedians living (in Kelly’s case at least) in London’s insalubrious neighbourhoods. But it’s London, so it’s relative.

In Tamsyn Kelly’s case, she comes from the nearest council estate to Land’s End — the contrast with the middle-class, Rick Stein postcard fudge-packet version of Cornwall was probably what hooked me when I saw her show recommended in the Evening Standard and I booked it in advance.

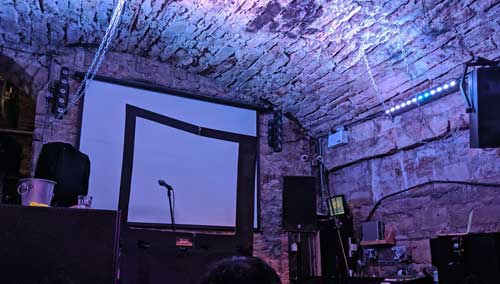

Seeing James Meehan was down to serendipity. I’d come out of Monkey Barrel, having seen Olga Koch (of whom more in another post) and walked along Cowgate collecting flyers. I don’t know if it was the person handing out the flyer, the flyer itself or me looking up the show online but I was interested enough to turn around at head back to Cabaret Voltaire — like the Caves an amazing subterranean warren of vaulted brick rooms. (I seem to have picked up he was a fellow Lancastrian somewhere along the way.)

Both shows were predominantly autobiographical — and both dealt with some bleak aspects of growing up in places marginalised and forgotten. Both comedians referenced cruel characters from their upbringing who’d been (possibly) brutalised by their upbringing. Neither did so with sentimentality — James Meehan performed some warts-and-all character sketches of people with indefensible attitudes from his the scene of his Leyland upbringing (framed as the worst online dating videos ever).

Not that either show was depressing or flat — there were plenty of laughs in both. There was a great audience participatory callback in Meehan’s show involving the world’s worst sex toy. Tamsyn Kelly ended her show in a way that was as far from self-pitying as is imaginable.

Both displayed an honest and appealing wit — and first-hand insight — into what divides the country into (some might say) a vibrant London and “the left behind” (if that can be interpreted as unsentimentally as possible. The shows made the point that privilege enjoyed by the likes of Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Jack Whitehall and a large number of similar others in the creative industries certainly doesn’t extend to any substantial percentage of the British population.

Both stand-ups used material to show that characters from their backgrounds could react to this either in a moronic or actually rather dignified way. Both comedians delivered amusing and though-provoking hours of stand-up with no sense of time-dragging or repetition, using visual aids and innovative changes of structure to vary the pace.