Sounds like some kind of Skyfall clone doesn’t it, but Agent Hunter is a new source of information that might be almost as valuable to aspiring authors as state secrets to 007. It’s a new website that has collated a huge amount of information on literary agents, agencies and publishers together in an online database. It also comes with a search facility that’s ingeniously configurable.

Agent Hunter is from the Writers’ Workshop — the people behind the very enjoyable York Festival of Writing that I attended last September. (I posted about the Festival here –and an edited version of the post has been included by Debi Alper in the book of the festival along with many entertaining accounts by other delegates — available for purchase for Kindle on Amazon.)

I ought to declare an interest in Agent Hunter before going on to review it. Harry Bingham, of the Writers’ Workshop, has given me (and other bloggers) a free year’s subscription to the site, in return for a review on the blog but there are no conditions attached on what I write — the comments below are entirely my honest opinion.

Now I’ve mentioned that it’s a subscription site, I’d better mention the cost upfront — £12 per year. You can get on the site to have a look around for free (accessing the database is what you need the subscription for) and also get a try-before-you-buy 7 day period before you get charged.

So, is it worth it?

To answer this question, you need to consider both the quality and organisation of information on the site compared to that available elsewhere on the web — and the value you place on being able to easily access it.

The traditional (pre-internet) method of finding agents’ and publishers’ details was to use a directory like The Writers and Artists’ Yearbook. Harry Bingham hasn’t set up Agent Hunter in competition to the W&A YB as he’s the author of two branded companion volumes — The W&A YB Guide to Getting Published and their How to Write guide. Also, the W&A YB takes a broader and shallower sweep across many creative industries (including journalism, photography and artists’ markets – as the name suggests).

Most crucially, the book is an annual publication (coming out in the summer before the year in its title) and, for prospective authors, only deals with agencies rather than individual agents. As hard-copy submissions (including that infamous SAE requirement) appear to be almost universally being replaced by online alternatives of some form, most writers now probably use the yearbook as a starting point to research agencies’ websites.

Largely being small enterprises (with a few big exceptions), agencies don’t tend to operate whizzy interactive websites full of bells and whistles (and some do have pretty basic sites) but most will at least list their submission guidelines — occasionally with automated ‘click here to attach’ links to make it easy for authors to submit to a central submission clearing system.

As well as lists of their clients, most agencies will also usually provide details of individual agents, maybe with a bit of a bio, along with the genres they’re interested in representing. When speaking to writers at events like conferences or talks to students, agents tend to stress how doing a bit of research on individual agents’ preferences is usually time well spent.

Often agencies are staffed by a mixture of senior agents with relatively full client lists and more junior associate agents who are much keener to trawl through the slush pile to find the Next Big Thing. If the agency’s guidelines allow it, these hungry agents appreciate being treated as individuals and contacted directly.

Conversely, a staggering proportion of agents’ rejections are for material sent to the wrong place — short stories, scripts, poetry, memoirs, sci-fi and fantasy (to a large extent) and so on tend to be handled by specialists and won’t be read by an agent who’s advertised a preference for, say, general fiction or romance.

So with all this information available on agency websites, what’s the advantage of using Agent Hunter? It largely depends on how much you value what else you could be doing with your time. Would you rather be writing your book than compiling a list of agencies and then trawling through the uneven content on agency websites? In monetary terms, the annual subscription, comes to just under two hours work at national minimum wage rates (sadly that’s quite a lot higher than the return on their time many writers achieve).

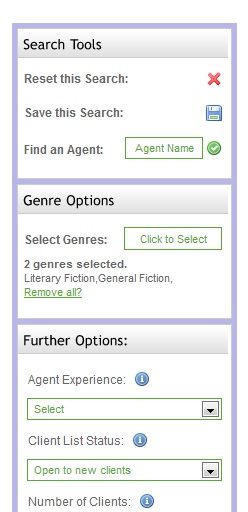

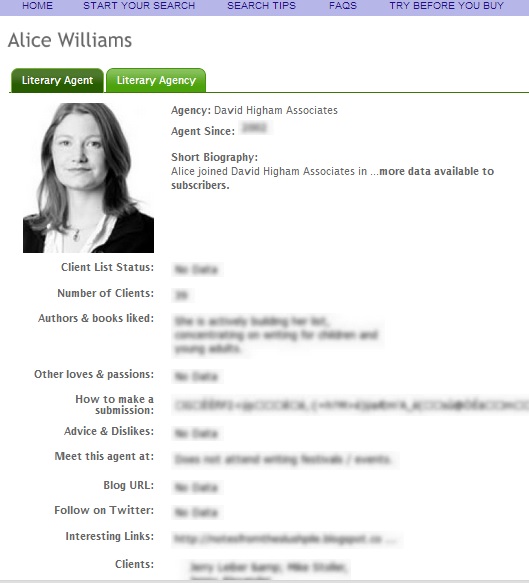

Agent Hunter also has an advantage that its information is potentially much more up-to-date than traditionally published sources. The database can also be more extensive and personal than the brief corporate CVs that often appear on agency websites. For example, extra biographical information can be added, Twitter names may be included, preferences such as whether agents appear at conferences and so on — see screenshots accompanying this post. (I think this line has convinced me that this particular agent might like my novel: ‘She likes the store Liberty, taxidermy and skulls’!)

Some advice on what an agent would like to see submitted (or not submitted) is also included on some entries, although it can be rather terrifyingly blunt. ‘Whilst we welcome genre fiction…we aren’t fond of writers who do nothing new with the established tropes of their chosen [genre]…We certainly don’t want to see books that we could have, essentially, read already.’

Or ‘Enjoys…stories with an emphasis on plot instead of endless pages of metaphor’. Damn, there I was, ready to submit my manuscript with its endless pages of metaphor until I read that!

There’s also some useful practical tips: ‘Slush Tip: Don’t send fresh produce with your submission. Currently reading a teen fiction manuscript splattered with exploded passion fruit.’

Another bonus is the uniformity of the data — making information from different agents much more easily comparable than with an online search. The database search is handy, for example, if you want to filter out agents who aren’t currently building their list or aren’t interested in your genre. There are many different ways the search can be configured — it’s almost like online dating for writers!

And, perhaps like online dating, the amount of material fluctuates wildly that’s supplied by agents into the public domain to interest possible suitors . Some may as well have written ‘bugger off’ and be done with it, while others have offered information that’s actually quite helpful.

On the other hand, social media may lead to knowing rather too much about an individual. In the few years since large parts of the writing community became some of the most enthusiastic Twitter users, it’s been possible to find out more than it’s probably advisable to know about some agents’ personal likes and dislikes. While it’s often very entertaining, and certainly diverting, to read about what meal an agent is eating, how their football team is doing, what outfit they’re wearing that day or to follow a Twitter gallery of photos of sleeping kittens, this information is likely to be filtered out in the Agent Hunter database.

Agents hate being pitched to on Twitter and some no doubt enjoy a bit of online interaction with potential clients. However, others are probably rightly cynical about the intentions of those who try to build up relationships via Twitter in the hope it might sway representation. At a talk I was at last month, one agent baldly stated that trying to cultivate any sort of relationship with a prospective agent was a waste of time — all they’d be interested in was the quality of a client’s writing, not the quality of their Twitter banter.

Interrogating the database to find an agent who’s right for you (at least theoretically) as an individual writer is a little empowering in a modest way — a welcome change from the ‘I absolutely, really, really must get an agent but how on earth will even one agent possibly read let alone like my writing out of the millions of others on the slush pile’ anxiety of the un-agented author.

As discussed in my MMU Text assignment, agents are now regarded, albeit at times unfairly, as gatekeepers to the traditional publishing word and, while I’ve met plenty of writers with agents who’ve yet to be published, for most types of book, having the representation of an agent is normally a prerequisite to getting a publication deal.

As part of an MBA several years ago, I studied corporate strategy for much less interesting industries than publishing. But publishing isn’t a normal industry. I sometimes try to reconcile the way publishing works with classic models of business theory — like Porter’s Value Chain where the raw material gets shoved in at the start and then everyone involved adds a bit of value and gets a cut of the profit. But at least the acquisition part of publishing (the research and development bit) works so counter to this that I risk getting bewildered into a brain meltdown — and need to remind myself (in the words of Mel and Kim ‘that’s the way it is, that’s just the way it is’).

But it’s interesting theoretically to compare different industry sectors’ attitude to research and development. A pharmaceutical company or IT software company might spend 15-20% of its turnover on research and development (R&D) — on the intellectual property to keep new and innovative products appearing in the future.

The publishing industry arguably has a negative spend on R&D if one includes the market for ‘how-to’ books, literary events, self-publishing fees, courses run by publishers and agencies (and more in the educational institutions that also run courses and the like). The industry (in a broad sense) makes money from people wanting to do its R&D for it, as well as inundating agents and publishers with so much unsolicited material that it’s referred to by terms like ‘the slush pile’.

Publishers and agents may well counter argue that the majority of published books, as well as investment in new authors, should be regarded as R&D or speculative marketing costs because so few sell enough to make a decent return — with the industry kept solvent by bankable blockbuster authors and the rare unknown titles that suddenly take off (either out of the blue or with the support of a prize or similar publicity).

This is probably the case for most of the creative industries — there are legions of musicians, actors, artists, dancers (even chefs, bakers and the like these days) who, like writers, are toiling away for the love of it but also hoping that their talent is validated and recognised (and necessarily risking the investment of that very fragile part of their ego in the judgement of others which is bound up in the endeavour of publicly exposing a creative project).

Even so, those lucky enough to get a lucky break also realistically know that even landing a good part or a recording deal won’t, on the balance of probability, lead to fame and fortune and giving up the day job. As with writers and literary agents, most equivalent creative types are represented by managers or agents who take a percentage of their income as payment.

However, it’s arguably unusual that in publishing the intermediaries that are funded by a cut of the artists’ income also perform the function as gatekeepers for those who risk capital in the enterprise (i.e. the publishers). In other aspects of their job, agents will have a potentially adversarial relationship with a publisher (negotiating a good deal) but, in sifting new talent, they perform a function on the publisher’s behalf.

Actors will audition for directors, musicians will be send in demos to A&R departments or be spotted at concerts or online by record companies — the representation by the agent or manager tends (at least to my incomplete knowledge) to come at the point where the artist has already been offered a commercial deal. Maybe there’s something particularly time consuming about the assessment of a manuscript compared with walking into a bar and hearing next year’s headliners at Glastonbury. (However, agents and publishers often say they can make a decision on the vast majority of submissions by the end of the first paragraph.)

Are actors turned down for audition because they don’t have agents or bands not signed because they don’t have managers (real bands, not ones put together by the likes of Simon Cowell and Louis Walsh)?

Bearing this model in mind, and knowing how most agents, even those who work closely editing their clients’ work, thrive on the deal-making side of their business, it’s perhaps not surprising that some agents are a little ambivalent about the talent-spotting role that publishers seem to have thrust upon them. This may be why agents are now quite enthusiastic about taking on authors who have a decent self-publishing track record — they’ve proved there’s a demand for their work and the agent can maximise the commercials. There’s a growing body of opinion that argues that a track record of self-publishing may replace the slush pile as a means of identifying new authors.

Certainly online communities that feature new writing (such as Novelicious) are attracting a lot of agent attention. I met a writer recently who was signed up by an agent on the basis of a serialised novel that she’d published for free on her blog (Emily Benet Spray Painted Bananas). And agents also keep a close an eye on other, more traditional, avenues, such as short story competitions.

But will I use Agent Hunter? Certainly. Although I have a good idea of the first few I’ll approach alreadyIt will be one of the resources I’ll use to draw up a list of likely targets once I’m finally there with a decent draft of the novel — and I’m not too far off — today I got some encouraging feedback from my MA supervisor on one of the last sections I decided to completely rewrite. Watch this space for details.

Harry Bingham read the post and sent me the following comments by e-mail (which he’s happy to have added to the blog).

I think most of what you say about the evolving industry is very true.

On the publishing as viewed through the MBA lens. Isn’t it that the slushpile is like iron ore: completely useless until smelted. And there’s a cost to find the ore. (You need an office, and a postal address, and a sign above your door that says ‘literary agent’.) Then you need to start the smelting, which means discarding the rubbish, working with what remains, etc etc. In that sense, there’s no more value in an unpublished manuscript than there is in a shovelful of rock taken from a gold mine. The shovel is probably worthless, but …

Anyway. Thanks very much for the article. These things help us enormously. It’s much appreciated.