As well as being the title of the novel, The Angel is also the name of the pub at the centre of the narrative. It’s a fictional village local somewhere in the Chilterns and, is a little like George Orwell’s famous Moon Under Water as it’s something of an idealised English country pub (at least in its appearance — thatched, whitewashed, low-beams, inglenooks, flagstoned floors). As mentioned previously, it’s not based on one particular pub but everything in it is an amalgam of real characteristics of about a dozen pubs in the Chilterns that I know very well.

Of course, the physical appearance of a pub is only part of its appeal — the set where personal dramas are played out. As anyone who’s visited more than a few pubs knows (in the country or city), it’s doesn’t take that much searching to come across some very idiosyncratic features — or strange activities that occur in otherwise ‘normal’ pubs.

Only a few days ago I visited a pub I’ve known for a while called England’s Rose in Postcombe, which isn’t that far from M40 junction 6. I’d naively assumed that the pub had borne that name for centuries but no — it was renamed from The Feathers almost exactly 16 years ago in 1997 after — you’ve guessed it — Elton John’s reworking of Candle in the Wind at Diana, Princess of Wales’s funeral. The pub had been converted into a shrine to Lady Di.

We were given a tour by the licensees. There was a whole bookcase of Diana-related literature in the main bar but the restaurant extension was where the Diana memorabilia had been most concentrated. Sadly quite a lot of the souvenirs had been thinned out in recent years but there are still rare photographs on the wall apparently presented by Mohammed Al Fayed.

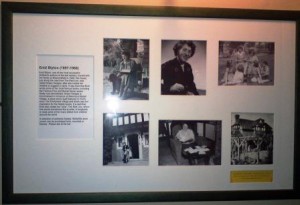

In a similar vein, although there is more of a geographical connection, the Red Lion in Knotty Green near Beaconsfield has celebrated the life of probably its most successful writer — the phenomenal Enid Blyton.

I say ‘probably’ because Terry Pratchett is said to have been brought up in the area, although he may have lived closer to the spectacularly ancient Royal Standard of England in nearby Forty Green. Huge though Terry Pratchett’s sales are, I’m not sure if he’s yet eclipsed the figures for the Secret Seven, the Famous Five and the rest of her vast backlist.

Fortunately, perhaps, at least for adult drinkers, the pub hasn’t themed itself around Noddy, Big Ears and friends. When I last visited a few years ago, it was more a collection of soft toys, books and a few photos framed on the wall. But it’s an example of how pubs can mark unexpected associations with their local communities.

On a more seriously literary note, the Pink and Lily pub on the scarp of the Chilterns near Princes Risborough, has a wonderfully atmospheric room devoted to war poet Rupert Brooke which is preserved almost exactly as Brooke would have drunk in it himself almost exactly a hundred years ago. Brooke does have a personal connection with the Pink and Lily, having written a poem about it and spending a lot of time in the area whereas I’m not sure if Diana ever drank in England’s Rose or Enid Blyton in the Red Lion.

Combine the oddity of pubs with their role as venues where the local community comes to mix and things can get very strange indeed. It’s always been an ambition of mine to visit some of the inexplicably weird traditions in some of the remoter parts of the country. The tar barrels of Ottery St. Mary are near the top of my list, although not strictly pub related, but I’m most curious to visit the completely bonkers Straw Bear Festival of Whittlesea — which seems to be the most surreal pub crawl imaginable.

But very peculiar entertainment is laid on in pubs closer to home. Below is a YouTube video I took at the Swan in Great Kimble during its recent beer festival (or Oktoberfest — which explains Mick, the landlord’s rather incongruous Lederhosen). No expense was spared in the provision of scintillating entertainment for the patrons — there was a nail driving competition.

For anyone unfamiliar with the idea (as I was) it is a stunningly straightforward contest. Two people with two hammers and two nails — and the fastest to knock their nail into the stump wins. Who needs 3D films, karaoke or even television when we can entertain ourselves like this?

But, in this clip, entertaining it definitely was. The two contestants are my friends Carl (on the left) and Simon. There are two separate contests but Simon is trounced in each one. The scepticism and bewilderment that Simon displays through movement and body language in checking Carl’s nail has indeed been driven in faster is pure physical comedy.

It’s a priceless little nugget that shows how British eccentricity still thrives if you know where to look for it.