The first part of my novel — and some of the later action — is set in Shoreditch. I first got to know the area when I was taking the City University Certificate in Novel Writing (now the Novel Studio). Although City University itself is about a mile or so west of Shoreditch (I know this as I walked the exact journey last week), it led me to start looking around adjacent areas of London.

I can’t remember whether I’d decided to write a novel with an artist as a main protagonist before I came across Village Underground (and its rooftop tube trains) in the Secret London guidebook. However, very shortly after reading about this artistic community space with an events venue underneath, I’d been up on the roof to visit for myself and had the start of a novel set in what was then, despite some creeping commercialism, a part of London that had a genuine alternative and bohemian feel.

What’s most fascinated about Shoreditch, as opposed to further flung artistic enclaves like Hackney Wick, is its location right on the edge of the City of London — in the novel this geographical closeness enables the two characters from completely different world to meet.

Apart from one residential block, the very unironically named Avant Garde tower at the corner of Brick Lane and Bethnal Green Road, there’s been surprisingly little encroachment by property developers exploiting Shoreditch’s position on the City’s northern fringes.

The Broadgate development (seen above) was completed in 2008 and, since then, the City seems to have grown upwards with the likes of the Walkie Talkie, Heron Tower, Cheesegrater and Shard (albeit on the other side of the river).

While the character of Shoreditch has undoubtedly changed with the arrival of the Overground and Shoreditch High Street station plus associated developments like Boxpark, the physical environment has changed little from when I first got to know the area (and probably hasn’t changed that much since the area was first industrialised).

I put this hiatus in development down to the delayed effects of the 2008 credit crunch and its consequences.

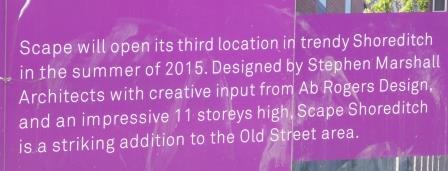

This is all about to change and, sadly for the Shoreditch I’ve come to know, I feel that the last few years will come to be seen as a stay of execution for one of London’s most characterful areas. As an example, since the New Year, the car park on waste ground opposite Village Underground seen in the photo above has seen construction activity begin — and it’s deep piling work that’s being carried out — of the type required for the foundations of very tall buildings.

Those who have been on street art tours of Shoreditch will know this car park as one of the areas that featured the most frequently changing graffiti art. Now it’s fenced off and will soon be transformed into a ‘mixed use’ development called Shoreditch Village — the first part of which will be a ten storey Citizen M boutique hotel, due to open by this time next year. For an artist’s impression of the finished site, click on this story.

This development is relatively modest but it will still tower over all the buildings in the immediate area — and will change the character of Village Underground. It used to be a quirk that the tube trains were, ironically, the highest point in the local area and, counter-intuitively, looked down on everything below. Soon all the trendy guests in the hotel will spy on them from above.

For a taste of what the area around Village Underground may look like in a year or two, then take a walk a mile or so to the area to the north and west of Old Street/’Silicon Roundabout’ (known also in the media as the risibly-named Tech City).

The area around the City Road Basin on the Regent’s Canal is undergoing a dramatic change with several huge, upmarket apartment blocks currently being constructed. This is a huge change for an area that, even when I was doing the City University novel-writing course, in 2009-10, was still genuinely down-at-heel and post-industrial, unlike Shoreditch. There’s even a drive-through McDonald’s there — which would be unimaginable down the road in Shoreditch.

Construction on one or two of the tower blocks was started, and then paused, during the recession and, like Shoreditch, the areas of derelict land and waste ground were likely to have been earmarked for development that was put on hold. But no longer. The construction has restarted and the place will soon change forever.

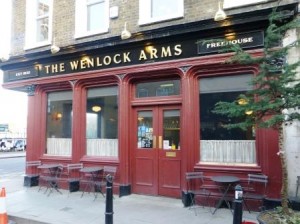

There’s a scene in the novel based in the City Road area, near the canal, as at the start of the book Kim works in a pub that’s based on the Wenlock Arms, which has near-legendary status amongst serious beer drinkers for being one of the very few basic, spit-and-sawdust, unreconstructed back-street boozer that wasn’t too far from a central tube station. in a location.

The Wenlock itself was victim to the gentrification of the area. It was closed a few years ago and was threatened with development into flats. After a landmark local campaign to get the pub protected by Hackney council (of which I was a supporter) it has now been included in a conservation area and has since been rescued and sympathetically refurbished. The holes in floorboards and barely functioning toilets have gone to be replaced by craft beers and trendy square hand-basins but it’s now thriving again.

Shoreditch Village is nothing compared with some new developments that are either in the pipeline or currently going through the planning process. Plans for the Bishopsgate Goods Yard site around Shoreditch High Street station are so dramatic that Hackney’s mayor (Shoreditch is on the fringes of both Hackney and Tower Hamlets) has started a petition on Change.org to protest to Boris Johnson about his decision in principle to approve them.

This is a massive development site, derelict for over fifty years after a fire destroyed the old railways goods yard that previously occupied the site. Shoreditch High Street station has been built on some of the area — and the reason why the railway is enclosed in a concrete box in the station is to allow building work to commence without disrupting the railway that runs through the site.

But the developers plans are equally huge — they include seven tower blocks, with two forty-six storeys high (much bigger than those pictured on City Road above). A little of this will be affordable housing but it’s inconceivable that the character of Shoreditch (and the Brick Lane area to the east) will remain unchanged with development of such scale encroaching almost into the heart of the area.

The likes of Pret a Manger and Pizza Express are one thing but, if the development is anything like One New Change, Cardinal Place in Victoria or the many in Canary Wharf, then there will be less galleries, oddball clothes shops and organic cafes in Shoreditch and many more familiar names from any high street.

It would be somewhere that my artist character Kim would never contemplate living or working in. And so my novel might, perhaps, have captured a particular moment in the development of Shoreditch — when it had established itself as quirky, creative and fascinating and when the hipsters could enjoy the place in almost suspended animation for a few years. Now it’s in danger of the City speculators moved in to kill the goose that laid their golden egg. Let’s hope not. Sign the petition.