The point from which this view can be seen is unique — with that tremendous triangular shadow — and it’s only been open a week. I must have been very lucky to have caught a moment where the sun was almost directly to the south of the Shard and low enough in the winter sky to have thrown that needle-like shadow long enough to cross the Thames and into the heart of the City itself. While I’ve reduced the resolution of the photos for quicker downloading, it can be seen that the tip of darkness points about a hundred yards directly east of The Monument — perhaps rather symbolic from the new structure in Southwark.

So — I couldn’t resist it. I splashed out my £25 and went up the Shard on Monday this week — only the fourth day the viewing platform, The View From the Shard, had been open. Well, I had to really, after all, I’ve been following its progress while it’s been under construction and charted much of its development on this blog.

This post isn’t entirely unrelated to the novel. A significant part of The Angel’s plot happens in places photographed below, which I’ll mention, and I suspect there’s something quite writerly about enjoying a view like this from high above.

But principally, this post is an unashamed Shard-splurge and, rather appropriately, takes up a lot of vertical screen space — but, if you’re on the home page and looking for other posts, keep on scrolling as it’s all still there — just a long way down (like the River Thames above).

I’ve thumbnailed seven photographs below from in 2011 and 2012, most of which have appeared on the blog. Taken from various viewpoints (anyone want to guess where?), the photos show the rapid pace of construction.

Here’s the Shard rising in 2011.

The viewing platform is lower than might be imagined. It’s on the highest of the steel floors that were slotted around the concrete core as it rose upwards. However, The pinnacle of the building (a considerable height as can be seen from one of the photos below) was prefabricated like a 3D jigsaw and assembled in Yorkshire before being disassembled and lifted into place on the top of the building.

Here are four shots from 2012. The crane has disappeared in the May photo but the lift along the outside remains attached. I was baffled at the time about how the crane at the top would be removed but the builders ingeniously erected a temporary crane on the side of the Shard close enough to the top to be able to reach up to remove the tall crane but accessible enough from within the building to be disassembled. Cranes fascinate me.

Sp the viewing gallery is around the point where the track for the exterior lift stops in the May 2012 photo. Even so, it’s very high, as can be seen by some of the pictures below, and it’s odd to think that slightly over a year ago the viewing platform was just empty sky.

The dreadful weather in London over the last couple of years is noticeable in the series of photos — there’s barely any blue sky in any of the photos — even those taken in the summer.

By contrast, I was lucky with the weather when I was actually on top of the Shard. Monday was a bright and breezy day. Imagine pre-booking several tickets at £25 to find that the top of the Shard was shrouded in low cloud — something that will happen. Looking at the website’s terms and conditions, it appears that the management has discretion to provide a voucher in lieu of future use in these circumstances.

Although the top floor of the observation area is open to the elements, there’s still a safe wall of glass extending well above head height. The combination of glass and light entering from all directions means the viewing area, particularly the higher level, is tricky for photography (at least when it’s bright — next time I won’t wear a light-coloured coat). Half the photos that I took aren’t publishable on this blog due to smeary reflections.

As its marketing suggests, the View From The Shard is a well-organised and a friendly experience, if the chatty lift attendants are anything to go by. Unlike the London Eye, where by definition your viewing time is limited, visitors can stay all day at the top of the Shard (although entry is by timed-slot). Much attention has been paid to the detail, with an interactive map of where the four viewing platform lifts are positioned and even specially woven London sight-themed carpets. There’s also a little gift shop seventy storeys up. But as I queued in front of a large video screen for the airport style security scanners, I didn’t expect to see the scene below:

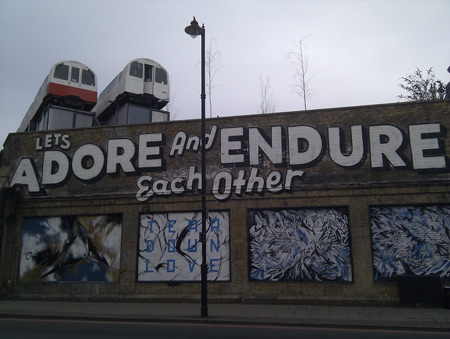

Yes — Village Underground’s facade on Great Eastern Street was entertaining the waiting tourists. (This is where Kim has her studio at the start of the novel.) It was part of a montage including Brick Lane and other ‘edgy’ urban attractions that shows how the urban street-art scene is now an established part of the London tourist experience. I asked Village Underground via Facebook if they knew their wall was being used as part of the Shard’s tribute to the capital’s culture — they didn’t but thought it was quite cool.

So, how far can you see? As this picture shows, I was able to get a hazy view as far out as Wembley, with a fuzzy glimpse of Harrow-on-the-Hill and the Chilterns beyond. The hills of Essex and the North Downs are also visible from other directions but I’d love to go up on an exceptionally clear day with a pair of binoculars and find out how far I can see.

One paradox of the view from the Shard is that it’s a high enough perspective to avoid all the buildings that normally clutter London’s sightlines. Take St. Paul’s Cathedral. Although it’s a little distant and the view is necessarily from above, in this picture it’s possible to imagine how St. Paul’s used to dominate the London skyline until the second half of the last century.

The St. Paul’s photo shows something of a parallel with narrative point-of-view. The height of the Shard gives an almost omniscient, third-person perspective — with enough information to see the big picture — how the components of the view or narrative relate to each other. And (with a camera or change in what Emma Darwin calls psychic distance) you can zoom in closer to the subject. But the trade-off of omniscience is distance and remoteness. Only by standing close to St. Paul’s can you appreciate its scale or touch the fabric of the building and feel its solidity. And to stretch the metaphor further, go inside the building and explore within.

A significant part of the plot in the London section of my novel occurs around St. Paul’s and the Millennium Bridge also features.This photograph shows the elegance and economy of its design — leaving very little impact apart from a silvery filament connecting both banks of the river.

And it serves as a great metaphor — linking the commercial Square Mile with the two cultural icons of the Tate Modern and Shakespeare’s Globe on the South Bank. The top of the photo also shows part of the new, incredibly long, Blackfriars station which extends right across the river. Note the solar panels that provide half the electricity for the station.

Having a camera with a (modest) zoom lens is obviously useful when you’re 300m up. Also, going back to locations in the novel, the below is a telephoto view of the bridge that takes the new Overground line across the top of Shoreditch High Street. The bus is at the end of Kingsland Road near the Geffrye Museum by a line of shops that features in a section of the novel connected with street art, although this piece might be one of the casualties of revision. I tried to spot Village Underground, with its tube trains on the roof but it appears to be hidden from the top of the Shard by the Broadgate Tower — which is at the extreme right edge of the photo.

Here’s the London Eye with St.James’s Park behind. Buckingham Palace is around ten o’clock — it’s quite a difficult place to pick out — I had to describe the location it to a family who were particularly looking for it. This shows that the London Eye is in a far better location for sightseeing, being much closer to the main tourist sites. Unfortunately for tourists, most of the view from the east and south sides of the Shard is devoid of landmarks, although I’m quite interested in looking at ‘ordinary’ London from the Shard. Even though I like the Shard, I’m glad it’s not been constructed slap bang in the centre of London — imagine how out of scale it would look next to Nelson’s Column or Big Ben.

It’s a shame the big beach volleyball stadium at Horse Guard’s Parade has gone. It would have been slap right in the middle of the photo.

The height allows you to get up close for unusually personal views of better known landmarks from a unique perspective.

Sadly the well-loved Gherkin seems to be in danger of being obscured, especially from the west, by its new neighbours under construction — the Walkie Talkie and the Cheesegrater. Both are seen in the photo below, although I’m not yet sure which is which.

Slightly to the west (the other side of Bishopsgate) is the building that was the tallest in the country for many years — Tower 42 (previously the NatWest Tower). The perspective from the Shard shows how much the new record holder looms so much taller.

(Tower 42’s story partly explains why the opening of the Shard gallery is such an event. When it was the Nat West building, it was severely damaged by a terrorist bomb. Terrorism was one of the reasons why other high buildings either closed to the public or never opened public observation areas at all — such as the BT Tower and Canary Wharf tower. Unlike many other cities, London had no public high level viewpoints, excepting restaurants and bars, until the Eye opened in 2000 — the Shard really is an innovation.)

The below picture also gives an idea of the Shard’s height — it looks down on the roof of Guy’s Hospital tower — which was one of the tallest buildings south of the river pre-Shard.

A sense of height is also given by the way the railway lines from London Bridge stretch out into the distance.

This view towards the north west shows how the BT Tower also stands high over Fitzrovia and Marylebone. In the bottom right there’s a good view of the Royal Courts of Justice and to the upper left the colourful, new St. Giles’s development stands out. (Maybe I should get a job as a London tour guide?)

From this high up, the Olympic Park seems relatively close to the centre of London — much nearer than Wembley, although the Shard’s position itself is skewed to the south-east of central London.

One of London’s most distinguishing characteristics is the meandering Thames — and the twists and turns of the river can be appreciating from the Shard as from no other perspective.

And yet the Shard’s summit is substantially higher than the public deck, although you’d have to have a hard hat and a remarkable head for heights to climb the pinnacle below to reach the very summit.

So, is it worth it? If you’ve got a morning or afternoon to spend and you’re interested with London’s geography already then you’ll be fascinated — but also if you just want to indulge a child-like sense of wonder of being so high above the rest of the city then it’s a unique experience. There’s something inescapably human about wanting to stand and look at a city in this sort of panorama. And, to bring it back to novel writing, think of all the many stories that are playing out down below.

- Panorama from the Shard