I have a short update to the story of the Wenlock Arms in Hoxton, mentioned below, which is relevant to the fate of many pubs across the country.

The Wenlock is a spit-and-sawdust, East-end style local (which looks from the outside rather like a more downmarket version of the Queen Vic from EastEnders). It’s typical of an urban pub style that would have been found on virtually every street corner in Victorian London. However, the triple threats of German bombing in the second world war, post-war redevelopment and the consequences of changing leisure time activites leading to changes of use have led to such pubs becoming increasingly rare. If the buildings still stand as pubs then they’re likely to have been either gentrified into ‘bar and kitchen’ gastropubs or be vile drinking dens full of pool tables and fruit machines.

Not so the Wenlock. Mainly due to the pub’s promotion of real ale from small and microbrewers and the consequent patronage of the members of the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) and like minded drinkers, the Wenlock has continued as a genuine community pub — for example hosting regular live music. The phrase ‘unspoilt by progress’ (used by Banks’ for their beers in the West Midlands) could be applied accurately to the interior, which appears to have been under an informal preservation order that has seen a moratorium on any discernible interior decoration — which to the generally stylistically challenged CAMRA members is seen as a Good Thing.

As mentioned in the post on Shoreditch, the Wenlock sits in an area that is on the fringes of the Hoxton-Shoreditch urban renaissance — had it been any closer it would probably have been converted to a bijou neon place called Bar Frottage or something. However, the economic winds of redevelopment finally reached the Wenlock and an application was made to Hackney Council earlier this year.

As suggested above, planning laws mean that there’s no requirement to request permission to change the use of a pub into a similar sort of establishment, like a bar or restaurant, so long as it’s used to sell food and drink. This has been why many pubs have been ruined by being turned into failed restaurants. You could probably turn a pub into a kebab house quite happily.

However, permission is required to change the use of the building to any other sort of commercial use and, particularly, for private housing. As the price of housing is so expensive in large parts of the country, particularly London and the South East, the physical building of a pub (or even just the land it stands on) can be worth far more as an asset than the pub will ever hope to generate as a business. That’s why so many pubs are owned by speculators or giant pub companies that securitise their property portfolios in the City in exchange for cash.

In the case of the Wenlock, developers wanted to build at least five apartments on the plot. These would no doubt have sold for well over a million pounds collectively — creating a profit that would probably take a back-street boozer decades to realise. Therefore, all but the most successful pubs in this country, are only protected from the raging forces of market greed by local planning regulations. In the case of the Wenlock Hackney Council rejected the change of use application and many locals and real ale supporters celebrated this in the autumn.

However, there is a loophole which those wanting to redevelop the Wenlock sought to exploit. Premises can be denied permission for change of use but, unless a building has listed status or is in a conservation area, then the owners can do more or less anything else to it — including demolish it. This tactic has been used ruthlessly in the past where pubs have literally vanished overnight when developers have sent in bulldozers at midnight. (The famous Tommy Ducks in Manchester was an example, which was razed to the ground one night in 1993 at 3am in the morning. This pub used to have women’s knickers pinned to the ceiling — I was once taken there after a school trip to the theatre by the teachers!)

The Wenlock was just outside the Regent’s Canal Conservation area and so its locals were disturbed to see a notice of demolition attached to the building at the end of November. This is apparently a technical process to inform the council of an intention to demolish a building and normally the council can only object to the method of demolition proposed (unless the building is listed or in a conservation area). So it appeared that the Wenlock was going to be turned into a patch of waste ground — with the presumed intention of later lobbying for the original residential development once the pub had become only a memory.

But the pub’s supporters mounted a huge campaign (there’s a Facebook group called Save the Wenlock, which I belong to) and mobilised a coalition of beer drinkers and lovers of vernacular architecture to lobby Hackney council themselves. The pub could have been demolished, as I understand it, from about the 22nd December.

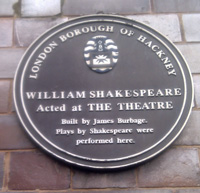

On Monday 19th December at a meeting of Hackney Council, the conservation area was extended to include the Wenlock Arms. The pub had been, possibly, days from demolition but has now been preserved — the fabric of the building and its permitted usage at least — whether the owners want to hang on to it with no prospect of it being anything other than a somewhat down-at-heel looking boozer is an open question. (There’s a very detailed historical and architectural account of the area — and an adjoining pub, the King William IV — on the council website.)

Fortunately there won’t be the traditional, short-lived rush to celebrate the preservation of an amenity that few people actually used — as happens often when economically struggling pubs are denied permission to change use. The Wenlock has never seemed to want for customers, which shows what a bleak outlook there is for less busy pubs when customers have less disposable income, beer duty is rising and inflation (especially utility prices) is rising fast.

As with most retailers, Christmas and New Year are the best times of year for pubs and there will be many publicans who will trade up until New Years Eve, bank the Christmas takings, and then shut down for good. The Wenlock’s success story is rare but it’s salutary and an example of what community action can achieve.