…ring the bells of Shoreditch in Oranges and Lemons, Shoreditch being where mos of the start of my novel is set, although I very much doubt the bells of St. Leonard’s are going to help me get rich by writing it. Â (The church is apparently features on current BBC series Rev, which is also set in Shoreditch.)

I’ve visited Shoreditch many times while I’ve been writing the novel, particularly recently, and I think I’ve noticed the most recent stages in its metamorphosis from run-down, working class area to the predominantly cool artists’ neighbourhood that it is today — although you don’t need to wander too far away from the Rivington Road/Shoreditch High Street area to find yourself in some very unartistic-looking, grim housing estates.

Perhaps the opening of Shoreditch High Street overground station about 18 months ago has been a catalyst as now the area is linked directly to south London and the North London Line at Dalston.

Shoreditch is surprisingly close to the City of London and its concentration of wealthy financial services workers. The photo below is taken from Shoreditch  — the marker post on the right side of the photo shows the City of London boundary marker.

It’s an extraordinary transition point with the Broadgate development on the right along Bishopsgate and the Gherkin in the distance. The street where I stood to take the photo is a very short length of road called Norton Folgate which connects Bishopsgate with Shoreditch High Street. It’s probably no more than one or two hundred yards in length but the contrast in urban landscape between its two ends is striking.

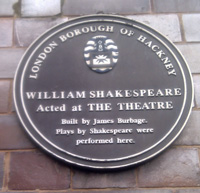

All types of disreputable activities occurred in areas like Shoreditch, just outside the City walls and, in the late sixteenth century, this included actors and playwrights, along with all the other undesirables cast outside the City walls like thieves and prostitutes. Just around the corner from Village Underground is this plaque in Curtain Road, which is a very understated memorial to the Curtain Theatre – a predecessor of the Rose and Globe Theatres in much more historically celebrated Bankside.

overground station laid right through it. It’s incredible to think that this area of Victorian warehouses, 60s office blocks and surface car parks was a crucible of the English language — where Shakespeare started his writing career.

Places like the Old Blue Last won’t have deterred the arrival of trendy artist types in the area and I thought the photo below shows an appropriate clash of old and new — über-cool American Apparel (apparently the shop where Ruta Gedmintas bought her outfits for Frankie in Lip Service) has opened up next to a pub improbably called the Barley Mow.

Actually the Barley Mow is only a traditional looking boozer from the outside, as I found when I organised a pub crawl starting at the pub, and found that the price of a pint of their Fuller’s ale was a far from working-class £3.70.

A group of us did 8 pubs in all in a route from Shoreditch to Islington via Old Street and the Regent’s Canal. Second on the list was the also archaically named

Bricklayer’s Arms (thought the punctuation of the name suggests there was only one tradesman).

On the crawl was the ultimate down-at-heel boozer that’s been the unlikely beneficiary of being turned into a nationally famous ale drinkers’ destination — the Wenlock Arms on the borders of Old Street and Hoxton.

It’s in a very mixed area with new apartments being developed around the Wenlock Basin on the Regent’s Canal but also being situated in the middle of the sprawl of forbidding-looking council estates that border the trendy centres of Shoreditch and Hoxton.

It’s an almost stereotypically ‘unspoiled’ pub — almost falling to pieces in places — but it’s got a thriving clientele of ale drinkers (some of whom I know seek this place out from the USA) but it has been under threat recently of being redeveloped into a five storey block of flats.

It’s the sort of authentic place deserves to be preserved and, as an example of one aspect of pub culture, a pub very like it might find its way into my novel. And any inquisitive barmaid who might work in this sort of pub would certainly know how to keep and serve great beer.