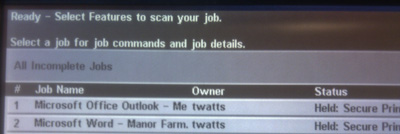

The user name below, found on an office ‘multi-function device’ (i.e. printer), appealed to my puerile streak.

I guess I shouldn’t laugh — maybe Mr Timothy or Ms Tamara Watts has had to deal with such sniggering throughout their lives — although the way computer user names are constructed to an unbending formula might prevent subtle ways of avoiding the construction. At least there’s a bit of ambiguity in the plural, I guess it’s even worse for someone with the surname Watt.

That particular piece of Anglo-Saxon vocabulary intrigues me as I was once pulled-up by an Open University Creative Writing student for using it in a screenplay writing assignment (and I suspect she deducted marks from the assignment in question). The objection wasn’t to the word itself — it was because I’d dared to put it in the mouth of a female character (in fact a prototype Kim).

She actually said that something along the lines of ‘a woman would never say that word’. (It might be an unwelcome consequence of feminism that many women — and I do think this is far more true of women than it is of men — seem to feel qualified to make sweeping statements on behalf of their whole gender group. It brings to mind Harriet Harman’s periodically facile assertions about women running organisations more effectively and compassionately — and in the next breath she denounces the uncaring destruction wreaked on the country by Margaret Thatcher.)

Every other woman who read that use of the word had no problem at all with it — so I don’t think it’s a gender issue — more of a generational one. Female baby-boomers, especially middle-class ones, have probably been conditioned by parents and peer-pressure not to swear in company but this doesn’t hold true for Generation X and Y — and especially not the generation who come after Y — whatever they’re called. (I’m a Generation Xer, by the way.)

‘The Angel’s’ characters straddle the boundary period between Generation X and Generation Y. (I’m using the most common definitions, according to Wikipedia, of X starting in 1964 and Y starting in 1982.) James and Emma are the tail end of the Xers, while Kim’s an early Y…and to some extent James will look at Kim as an example of a new, exciting generation (even though she’s not much younger).

But both the female Xs and Ys will swear a lot (I’m also going to have a woman Baby Boomer character too, who won’t). In fact the dialogue in the novel is so full of swearing that it breaks one of the cardinal Rules of Creative Writing that you tend to find in books — readers don’t like reading lots of profanities.

I’m not really sure about this rule on a couple of counts.

- I can see dialogue in which every other word is effing and blinding will be tedious but some of the most captivating speakers I’ve listened to in real life use frequent swearing in an expertly oratorical way — to contribute to the rhythm of a phrase or for comic timing — think of some of the most popular stand-up comedians.

- As with their reactions to sexual content, or something similarly taboo, what people say they think about a book/film/play/artwork is not necessarily what they think privately about it. I’ve blogged before about this issue might prevent honest discussion of a piece of writing in a workshopping situation — where it’s human nature for participants to use their feedback to reveal or conceal aspects of their own characters or experiences to the other participants.

- The advice might be sound in that it points out the costs of alienating a significant portion of a writer’s potential readership. However, if you worry too much about offending people as you’re writing then you may end up with a story as inoffensive, uninteresting and utterly bland as if it had been written by a focus group.

So Man Utd 2 Norwich 0 is my excuse for not getting that much writing done today.