…ends up in my novel. This may be something of a surprise seeing as most of it is set in an English country pub which, apart from the copious amounts of booze drunk, is probably one of the places least like Las Vegas in the world.

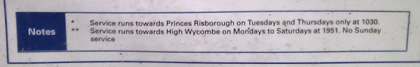

However, as has happened throughout the writing of this novel, what I’ve ended up doing in real life tends to have muscled its way into the narrative. The problem is that I’m taking so long to write the thing that the danger is that the plot I started out with will be crowded out with bizarre and incidental links to what else I was up to over the two years that it will have taken to finish (I have to be optimistic that it will be completed by Christmas — well, first draft, maybe?).

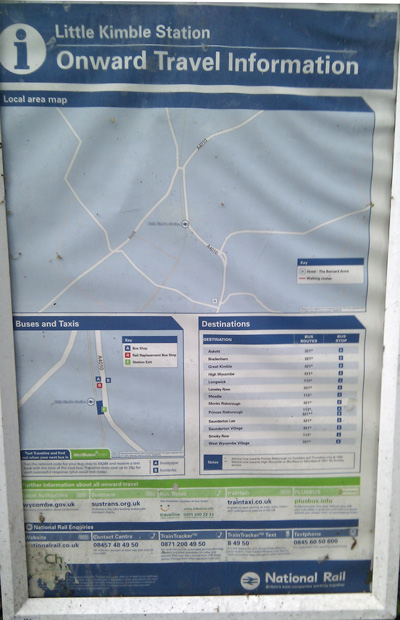

I’d like to say that the horribly long period between this post (written on a slow, stopping Chiltern Railways train in the dark) and the last (completed on a balcony in Santa Barbara overlooking the Pacific) was due to many words being committed to Microsoft Word but the time has mainly been spent enjoying the rest of the holiday (of which more later), getting back to work with the commute made more grinding by Chiltern Railways’ horrible new timetable – improved only for people north of Leamington Spa it seems – and doing all the tedious stuff that normally arrives in September.

But, as mentioned in my comments on the last post in response to Bren Gosling’s enquiries, I’ve come up with a whole load of new ideas for the novel. Some are wholly extraneous, irrelevant and (quite possibly) completely gratuitous but others serve to provide some missing context and backstory and to provide a bit of extra complexity to some characters.

And so to Las Vegas. This was the last stop on the holiday and I’m probably one of the last of my friends to have visited the place.

We arrived by car from Arizona and the Grand Canyon and, as I got the first view from the freeway about 10 miles away, I was quite prepared to dislike the peculiar cluster of high-rise buildings on the Strip, completely out of scale with the low-rise sprawl beneath.

Through a combination of special offers and me haggling at the reception desk for a pair of rooms with a connecting door, we ended up with a suite and adjoining king size room on the 39th floor of the brand new Cosmopolitan hotel. The combined floor space was probably bigger than my house. Whereas the view from my house is of green fields and the rolling hills of the Chilterns behind, the view from the three (!) balconies we had in Las Vegas was of the Eiffel Tower (at the Paris casino), Caesar’s Palace, the Flamingo, a glimpse of the campanile tower at the Venetian and the amazing Bellagio fountains. We were too high up to hear the music (maybe a blessing) but the synchronised show was a spectacle nevertheless.

As well as being very well appointed and luxurious, the hotel room had some unexpected bonuses – a washing machine and tumble dryer were very useful for people who’d been living out of suitcases for two weeks. So rather than a bottle of champagne in an ice bucket and some caviar blinis, room service delivered us a free packet of washing powder!

This was all very serendipitous research for the novel. As some of my ex-City friends might remember a piece I workshopped with Alison last autumn where Kim and James end up in a penthouse suite in a luxury hotel in London. If anything, the Cosmopolitan was larger and better appointed than the almost surreally sumptuous suite I imagined my characters stumbling into — it even had several plasma screens that controlled the music, lights, door locks and so on as well as being TVs.

I walked around photographing the suite and then also video recording it to keep for research (even the three toilets).

I’ll resist the temptation to make art follow life too slavishly and avoid writing into my novel a scene where Kim makes use of the facilities and puts her smalls in for an overnight wash and dry cycle (although, at that point in the story, she’s not changed for 36 hours so she probably ought to).

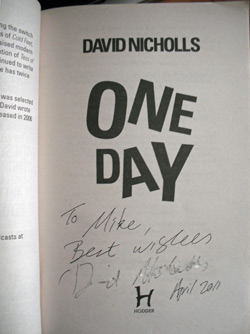

Another Las Vegas experience that may make its presence felt in the novel is the Beatles/Cirque du Soleil Love show at the Mirage. This is something I’d wanted to see since its inception about six years ago but never really thought I would – bar a transfer to the UK. Some of the remixes in the soundtrack album ‘blew my mind’ (to paraphrase one of the songs featured) when I first heard them.

It was a superb show but, being along time worshipper of the Beatles music, I was most interested in the surround sound – having Paul McCartney’s harmonies on Come Together come out from speakers behind your ears is a memorable experience.

The Beatles have some very strong German connections: John Lennon is often quoted as saying ‘I was born in Liverpool but I grew up in Hamburg’. This German influence on the outlook of one of the best-known Englishmen and shapers of popular culture in the 20th century won’t be lost on Kim – who’s a devout Anglophile but also has the patriotic fervour of the ex-pat.

Las Vegas – or the Las Vegas of the Strip – is such a ridiculously OTT monument to artifice that, a little like my reaction to Disneyland, the place couldn’t be viewed ironically – it ridiculed itself. I was awed by the scale and audacity of the place – a pyramid, a recreation of the New York skyline, a casino with an erupting volcano outside it and, perhaps most bizarrely, a monorail system of all things.

The whole place is a fiction – an attempt to paint audacious, and convincing, narratives to disguise the low-level, slot-machine routine gambling that provides the casinos with the cashflow that is the life-blood of the city.

But, ironically, it’s a fiction that isn’t executed in a tacky way. A lot of money is spent on exactly sourcing the right sort of materials to create a pyramid or the Manhattan skyline or similar.

Kim would know that one of the key figures behind much of the extravagant architecture on the Strip is Steve Wynn, who’s used his fortune to buy a lot of valuable modern art (though one of his acquisitions lost much of its value when he put his elbow through the canvas).

The all-you-can-eat buffets in the hotels also emphasise how Las Vegas is built on human fallibilities – greed being one, but also (obviously) gambling and  sex is suffused throughout the city. It never seemed to be far from the surface in Las Vegas – whether the organised touts on the Strip with their ‘Girls To Your Room in 20 Minutes’ T-Shirts (incredibly I saw someone wearing one of these as a souvenir at the airport), the risqué shows (including one Cirque du Soleil one) or the general atmosphere of a perpetual stag or hen party – thronged with gangs of hardly-clothed young people, although no-one is going to be comfortable completely covering up in the 40C temperatures we experienced.

It’s no wonder, despite the Strip’s relatively recent transformation in the 1990s, that Las Vegas has come to occupy its own niche in the pantheon of popular culture — many novels and films mine use it as a shorthand to access fallibility and excess.

But despite the hedonism, there’s also an appreciation of real beauty and culture – as in the opulent setting of the Venetian with its ‘real’ gondolas — its artifice is a step up from the fibreglass reconstructions in theme parks. The first time I walked into the recreation of St. Mark’s Square I gasped at the incredibly lifelike blue sky. It’s such a ridiculous conceit to reconstruct a water-bound jewel of the Renaissance in an American desert that it’s completely seductive — and you’re soon on the water being serenaded past Dolce and Gabbana and Louis Vuitton. I can see how Emma would fall in love with this place in a second.

It’s a fiction writers’ dream – a fantastical place that is motivated by, and appeals to, all the human desires that are normally kept hidden by the inhibitions of  society. I was so fascinated by the place I bought a couple of books when I got back on the development and history of the Strip — and I’m fascinated by the psychology of manipulation that is used in casino design.

It’s almost a cliche that there are no clocks or windows in casinos (although there are big windows at the new Cosmopolitan) but there are many other subtle triggers that are used to manipulate customers’ behaviour (perhaps no more than in a supermarket but it’s better to end up with too many buy-one-get-one-frees than to have your bank account cleared out). There must certainly be parallels with fiction writing and narrative.

So, despite, or perhaps because, my novel is largely set in such a supposedly staid and traditional place, some of the characters will be seduced by the idea of Las Vegas – it would be the sort of destination that both James and Emma would visit on their own stag/hen dos and probably go out for a long weekend in the winter.

And if anyone goes on holiday to Las Vegas during the course of my novel then you know that something interesting is going to happen — and what happens in Vegas isn’t necessarily going to stay there.