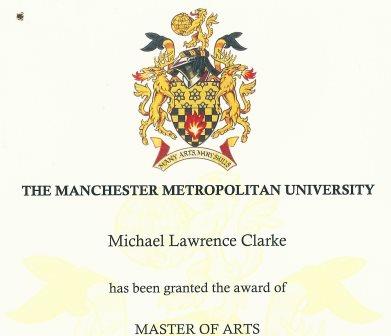

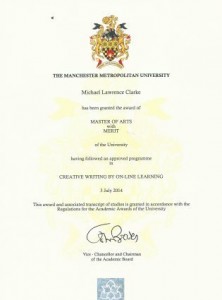

It’s been so long (over a year) since I submitted the final draft of my dissertation (i.e. novel) for marking by Manchester Metropolitan University that it was quite a surprise when a stiff-backed envelope arrived through my letterbox a few weeks ago.

So, documentary proof that I’m a qualified creative writer. Unfortunately, rather than being framed and displayed on the wall (apparently toilets are meant to be the place to hang these things for the ironically self-deprecating of us) the certificate is still languishing in a big pile of other post and papers (lots of not-so-nice things like credit card bills).

Such is the course structure, I’ve had plenty of opportunities to celebrate before receiving the official certificate: when I submitted the final draft; when I received the results of the dissertation, meaning I’d passed; when the examination committee sent me a letter saying they’d ratified the marks and I’d officially graduated. I could have attended the graduation ceremony at the Bridgewater Hall in Manchester but, having done the whole thing online up until that point, I decided to celebrate my graduation virtually instead.

Of course, the question now is how much doing the MA has advanced my writing career compared with the JFDI school of just getting my head down and writing — something many other writers have been hard at doing in November with NaNoWriMo.

I’ve meant to try and commit to NaNoWriMo myself for the past couple of years and had hoped to do this year. Whether I’d complete the 60,000 words in a month would depend on balancing my perfectionist instincts to go back over a piece of writing and revise it several times with my ability to bang work out to a demanding deadline. (I can work at a fast pace right up to a deadline as I did with the stories I had performed at Liars League stories, which were submitted just before the midnight cut-off on submission day and I can quite happily draft up 1,200 words in a couple of hours, as I did at last weekend).

I’m sure NaNoWriMo works for many people because it provides a similar sort of external pressure which is probably the second most valuable aspect of having done the MMU MA and City University course (and the OU and various other courses before that). If something has to be submitted by a date then the tendency to hone the writing by making lots of small incremental changes can’t be indulged indefinitely. The most valuable aspect of doing the courses has been, of course, the wonderful feedback that is generously given by peers and the expert recommendations of the tutors.

Nevertheless, an MA in Creative Writing is less of a guarantee of gaining a foothold in a profession than probably any other higher degree. While study and passing assessments and exams are necessary to join professions like the law, medicine, accountancy and many scientific specialisms, the path to becoming a ‘proper’ writer is much less clear cut.

In fact, when you talk with writers, the definition of when you actually become a writer is often rather nebulous and open to interpretation, partly because so many people who’ve published a book (or maybe lots of books) still have to work at their ‘day jobs’ in order to make a reasonable living. (One agent told me that he though it was odd to the point of endearing that lots of aspiring writers talked about their ‘day jobs’ — because so many published writers have other careers that it’s quite a rarity for any writer’s day job actually to be writing for a living — or writing fiction, at least, as opposed to journalism, copywriting, etc.)

So the time and money spent getting an MA in Creative Writing isn’t going to gain you automatic entry into the writing profession, however one defines that.But what it ought to do is equip you with the techniques, tools and, probably most importantly, the practice to make you more capable of writing a novel (or poem or play or memoir — whatever the genre) that will stand a far better chance of reaching an audience. I’d guess that the people who say they’re content to write solely for their own pleasure are probably less likely to go through the course or writing group approach because of the need to share your work with an audience whose opinions on it (not always positive) are discussed in detail.

In my case, and I suspect for most other students too, it’s gaining an audience for your work that’s one of the biggest attractions of a course — both in the direct sense of the feedback from tutors and other students and the indirect sense of training you to write work that’s capable of reaching the reading public.

Any decent creative writing course will also teach you that to reach that public (at least for the traditional publishing routes) the first step is to find representation by a literary agent — and an agent presentation is usually part of an MA course and they will often turn up at end of course readings and the like. However, the biggest concentration of agents in one place is at writers’ conferences, such as the York Festival of Writing or the similar festival in Winchester.

A few weeks ago I was lucky enough to win the prize of lunch at Edwins, a very nice restaurant in Borough High Street, with Isabel Costello through a competition on her excellent blog The Literary Sofa, which has been mentioned in one of my previous posts. Isabel was signed up by agent Diana Beaumont of Rupert Heath as a direct result of attending last year’s York Festival of Writing. Over lunch I had a great opportunity to ask Isabel about her experiences of the past year as an ‘agented’ writer. Coincidentally she wrote a very honest and informative post on this subject on her blog, which generated an astonishing number of comments.

It’s a fascinating and upbeat read about Isabel’s relationship with her agent (although some of the long list of nearly 100 comments could potentially be subtitled What They Don’t Teach You on Creative Writing Courses). I won’t paraphrase the post here but the original post (and the many comments) highlight how the publishing industry currently works. There are many talented writers who’ve written great novels which, even with the committed and enthusiastic support of their agents, haven’t been sold to publishers. (And because agents get a commission on their authors’ earnings, they don’t make a penny if a novel’s not taken up, despite potentially spending a considerable amount of time working on a book with a client.)

That said, of all the writers I’ve met who’ve not yet had a book taken up by a publisher (as opposed to those whose novels have been published or are already in the pipeline) the only one who I know has achieved a publishing deal for definite is a friend from the MA course (more details on that great news next year). Of course it’s likely that some of my ‘agented’ friends have some good news that’s under wraps or whose novels will successfully negotiate the slow-moving machinery of the publishing industry but that known success is a positive testament to the MMU MA.

(I haven’t forgotten that one of my City University coursemates, Jennifer Gray, has

published an extraordinary number of excellent, and well reviewed children’s books over the last couple of years — Atticus Claw, Guinea Pigs Online and the chicken books — but Jennifer had these moving along the pipeline when we met on the Certificate in Novel Writing.)

Reasons why books are sold or not can be very capricious — often reflecting what’s selling in the market at that moment (‘I want the next…’) based on factors that writers can’t influence, bearing in mind the time spent writing a novel (even the most ardent NaNoWriMo fan would concede that a novel written in a month represents a first draft that will benefit from much revision).

What Isabel’s blog post mentions is the importance of the hook or concept in selling a book to an agent (a subject that I used with respect to the film world in my Liars League story Elevator Pitch). She says her new novel, of which she’s just completed the first draft, is more focused on the hook than her first was (perhaps the benefit of discussion with her agent) but I’m sworn to secrecy about what it is. Isabel’s experience in this respect might be more valuable than elements of serious creative writing courses because, in my experience, these focus more on developing skills and competences in one’s writing in a way that can be applied to the prose and to the structure of the novel itself.

Courses are largely agnostic about the subject matter of a book. If you want to write a precisely observed story about, say, people sitting on a sofa watching TV in a suburb of Manchester then that’s fine, as might be writing about a civilisation-threatening invasion of supernatural zombies from another dimension. Talk to an agent and they might not only help you develop a novel with a killer hook but point you in the direction of the type of killer hook that’s snagging editors.

I’ve sometimes wondered why editors or agents, with their knowledge of what’s hot in the market, don’t use a Hollywood screenplay model and hire a bunch of talented writers to write a blockbuster to order. I guess there’s at least three reasons:

- No-one’s actually that sure what will work in the market or how long a trend will last — certainly not sure enough to pay people up front to write a book on spec.

- There are so many unsolicited manuscripts arriving from aspiring writers anyway that enough publishable and marketable books with irresistible selling points will be submitted anyway

- That writers, agents and editors see books as something more than commodities to be marketed – that they’re intensely personal to both reader and author and that the success of a novel is more about serendipity and catching the Zeitgeist than any carefully designed marketing plan.

And if number three is the most overriding of reasons then that’s, in my mind, another justification for taking the writing course route. If there’s no way of second guessing the market (and no winning short-cuts for attracting the attention of agents and editors) then the only way to do so is to write what you feel you have to write from the heart and make sure you’re practiced enough at the craft of writing to do the novel justice. I’m hoping the process of gaining the certificate proudly displayed at the top of the post will have taken a considerable way along the road to achieving that level of skill.

I’d love to hear other writers thoughts on MAs (worthwhile or an academic distraction?) and I’ll happily answer any questions put in the comments section on my own experience.

As a sad postscript to the post above, I was very saddened to hear about the death of one of my previous creative writing teachers, Dinesh Allirajah. Dinesh was a tutor on an online course I took with the University of Lancaster in 2009 that bridged the period between finishing my Open University Advanced Creative Writing course and the City Certificate in Novel Writing. I remember that his extremely positive comments on the prose fiction I submitted in my portfolio was one of the first pieces of feedback that suggested to me that I’d be capable of writing a novel. Dinesh kept up a blog throughout his illness, which he catalogued with fortitude and good humour. His last post can be found here. He was only, I believe, in his forties and he leaves a family with teenage sons. His legacy will hopefully live on through the many students he inspired.